|

Document: Matthew B. Brown's Remarks on "Solomon Spaulding and the Book of Mormon" Source: "Ask the Apologist" at FAIR Web-site |

"Ask the Apologist" screen-shot from FAIR Web-site

Copyright � 2003 by The Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research.

All Rights Reserved. No portion may be reproduced without express written

consent of FAIR. -- ("fair use" excerpts only provided here)

See also: R. & R. Brown: Downloadable free copy of TLIWTD#2

FAIR Guide: Spaulding Theory | What is the Manuscript Found?

|

Ask the Apologist Q. I have heard that Joseph Smith plagiarized the writings of Solomon Spaulding to produce the Book of Mormon. I know this has been refuted before, but can you help me understand this issue and get to the bottom of it? A. (by Matthew B. Brown) When the Book of Mormon was first published in March of 1830 its detractors believed that it did not have a divine origin as claimed, but was an impious fraud perpetrated solely by the Prophet Joseph Smith (who was listed on the title page of the book -- in accordance with federal copyright law -- as the "author and proprietor"). (See the FAIR web-site for remainder of text) |

|

Dale's Comments, Part 1:

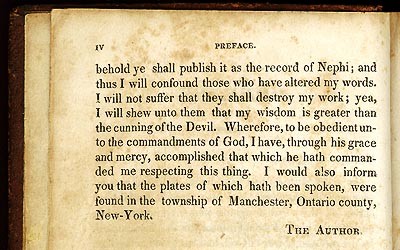

As I was Going to the Fair... The interesting thing about visiting the F.A.I.R. web-site is that I never know what next I'll find there -- or how long what I do find there will remain on-line. That's why I just made the screen-shot of FAIR's latest "Ask the Apologist -- Solomon Spaulding and the Book of Mormon" addition and placed it at the top of this web-page. If history repeats itself and the page content suddenly changes (as it did with one of their Robert and Rosemary Brown pages -- see my old screen-shot), I want to be able to keep Matthew B. Brown's remarks, as originally posted, in front of me for future consultation. I am assuming this Matthew B. Brown is the author of the faith-promoting All Things Restored and the same "Matt Brown" whose work the Director of the Kirtland Temple Historic Center once spoke well of, and not, perhaps, some close relative of apologists Robert and Rosemary Brown. In reading Matthew's on-line remarks, I'm pleasantly surprised that he resisted any initial temptation to simply rehash a few paragraphs from his namesakes' dreadful descriptions, and say his questioner's query has been answered. Considering what has been written by some faithful Mormon defenders in the past, I must say that I feel Matthew has done a much "fairer" job than some, in giving us a modern reply to that nagging old question: "Did Joseph Smith plagiarize the writings of Solomon Spalding to produce the Book of Mormon?" First of all, let me say that I hope the quoted query was an actual question posed by a real person, and not just a self-serving statement with a question mark appended, written up to give our apologist an excuse to "get to the bottom" of "this issue." A little bird recently told me that a major publisher in Missouri is releasing a book about Spalding, etc., and it would be rather naughty of my LDS friends to fire a preemptive shot across the bow of an enemy boat before it leaves dry-dock. On the other hand, perhaps a critical review or two of Matthew's recent reflections can help him and others hone their skills (and supplement their sources) in combating that tenacious "Spalding theory" one more time. Secondly, I really should make note of the fact that Matthew's inquisitor only asked for help in understanding the issue -- he (or she) did not really ask our good apologist if Brother Joseph had been so mean as to appropriate material from poor old Mr. Spalding's manuscripts, way back before the truth sprang out of the ground and all of that latter day stuff. Not much overt "combat" in this approach, and I must say, I really do like FAIR's new "kinder and gentler" rejoinder to the Spalding-Rigdon claims; it leaves a few windows open, just in case the air gets too hot in the apologist's chambers this time around. Consulting the Feb. 2003 issue of the on-line Fair Journal, I see that Matthew's remarks on the Spalding-Rigdon claims are getting the same high level attention as are seminal subjects like "caffeinated beverages." Maybe that's progress, and the next thing we'll see from the scholarly dilettantes in Deseret will be an article on how to read "View of the Hebrews" without breaking the Word of Wisdom. But enough of my insipid introductory remarks -- let's get to some real "meat," the kind we can blamelessly chew upon during the famine of a frigid February. "Author and Proprietor?" Our well-meaning apologist sort of gets off on the wrong foot, at the very beginning, where he says that Bro. Joseph "was listed on the title page" of the 1830 Book of Mormon, as the "author and proprietor" of the work, "in accordance with federal copyright law." The Seer of Palmyra might have just as well signed off simply as "proprietor" when he submitted his title page facsimile to R. R. Lansing, in Utica, back in 1829. Had he done so, he could have saved all of us Latter Day Saint apologists (yes I still lay hold to that troublesome title) a great deal of embarrassment through the ages, as we've tried to tell confused readers that young Joe did not actually write that book 1 Fawn M. Brodie's assertions to the contrary notwithstanding. But, that's a minor lapse. We can excuse Matthew of that slight incongruity and move on to more interesting matters. Is it really true, as Matthew says, that "When the Book of Mormon was first published in March of 1830 its detractors believed that it... was an impious fraud perpetrated solely by the Prophet Joseph Smith"? I wonder... I won't pile up all the relevant citations here, but I do believe I recall reading a whole stack of very early periodical articles telling folks that Sidney Rigdon, Oliver Cowdery, or a secretive "lawyer" from round about Palmyra concocted the thing. Wasn't it Jonathan A. Hadley who wrote in 1829 that "it appears not a little strange... that a person like Smith (very illiterate) should have been gifted by inspiration" to bring forth the book? Hadley was a Palmyra editor who lived within walking distance of the Smith cabin and knew Martin Harris personally, yet he says nothing about any local rumors claiming young Joe as the book's author. A few years later Hadley clarified his position on the matter, by saying that "An old manuscript historical novel, the property of a deceased clergyman in Pennsylvania, had previously fallen into Jo' s possession... The "translator," whether Cowdery or some other person, dressed up this old manuscript, merely adding to it whatever the Book of Mormon can be said to contain of a religious cast, and adapting its general phraseology as far as possible to that of the bible; but preserving the general original narrative..." Well, that was one man's opinion, I suppose, but it seems that Hadley and most other attentive "locals" never considered blaming young Joe for creating the Nephite Record. By the way, if anybody is interested in consulting all those very early citations, I mentioned, you'll find a bunch of them, laid out more or less in chronological order, in my review of Dr. Terryl L. Givens' recent book. Yes, yes, there were folks who thought that young Joe wrote the text, but most of his neighbors knew him well enough to laugh at that kind of idea. Once the book was published and more people could read its title page (first printed in 1829), it was natural for editorial commentators (such as the reviewer in the Rochester paper of Apr. 2, 1830) to say things like "The 'author and proprietor' is one 'Joseph Smith, jr.'" But, even there, the reviewer places author and proprietor between quote marks, as though to say, "the ostensible author and proprietor." I see no railing here (or in other contemporary sources like the Sept. 2, 1829 Palmyra Reflector) against the young Seer for being the "sole" perpetrator of the so-called "impious fraud;" in fact, Abner Cole, editor of the Reflector, referred to Smith as "that spindle shanked ignoramus," not a title well bestowed upon the author of a 590 page history of ancient America! Knowledge of Smith's childlike illiteracy seems to have been widespread at an early day. Orsamus Turner (another local newspaperman who later had more to say about the subject) stated in 1831 that "the founder of Mormonism is Jo. Smith, an ignorant and nearly unlettered man living near the village of Palmyra." Again, Turner does not pin the blame on young Joe as the "sole" perpetrator of the "fraud." When he added to his assertions, in 1850, Turner, like Hadley before him, felt that whoever produced the Book of Mormon was substantially "aided by Oliver Cowdery," and he did not mean Cowdery served merely as a scribe. Still, it must be admitted that Turner received the impression that the book was "a production of the Smith family" and not the work "of an educated man or woman." Despite the book's literary shortcomings, Turner was probably wrong to dismiss it as "a strange medley of scripture, romance, and bad composition," crafted by Mother Smith, a few of her brood, and cousin Cowdery. If Matthew is seeking a little support for his notion that folks were pointing at young Joe being the book's "sole" perpetrator, Turner's accounts provide no aid and comfort for that notion. People who actually lived in the area and had some reason to monitor events thereabouts, knew that the Palmyra Seer could barely read during the 1820s, let alone write a coherent paragraph. Today we can buy the BYU Studies stack of documentary DVDs, spin the discs in our computers, and view examples of Bro. Joseph's horrible early penmanship for ourselves -- it's a scary experience. Obviously those people who accused our Seer of scripting the Nephite Record either were totally unaware of his limited literacy, or had heard tell he had a few educated scribes at his command. So, unless Bro. Matthew can come up with a few supportive sources, I think we must agree that when young Joe and his friends left New York for Ohio at the beginning of 1831, he departed under the cloud of having been the primary promoter of the so-called Gold Bible fraud -- not as having been the writer of the book. As Abner Cole said, on Feb. 28, 1831, when the Mormons were departing the Empire State: "There remains but little doubt, in the minds of those at all acquainted with these transactions, that Walters, who was sometimes called the conjurer... first suggested to Smith the idea of finding a book." Smith, the fraud-finder? Yeah, his neighbors could swallow that idea. Smith, the final editor of the golden plates? Perhaps. But Smith, the pseudo-scriptural author? No way! Even if young Joe (or one of his family or delinquent pals) did compose the thing, would that necessarily have made the coming forth of the "fulness of the gospel" an "impious fraud?" The Rev. Dr. William H. Whitsitt, for one, didn't think so. He no more believed in Nephites than he did in Neptunians, but Whitsitt was prepared to give the early Mormons the benefit of the doubt and he referred (in his biography of Sidney Rigdon) to the Gold Bible as a "pious fraud." Now there's a notion that Liahona LDS, Signature Books Saints, Cultural Churchgoers, and those Rebellious RLDS can cozy up to. Why, shucks! The Almighty just works in mysterious ways to confute the wisdom of "the learned" in these latter days -- that's all. If you want to read a reasonably intelligent early review of the Book of Mormon, consult the one written by Walt Whitman's brother, back in 1834. The reviewer writes under no illusion of the book being historically genuine -- he says it "is with some art adapted to the known prejudices of a portion of the community" as it existed in Jacksonian America. But Jason Whitman was sagacious enough not to charge Joseph Smith, Jr. with writing the Nephite Record; he leaves the authorship question an open one. Whitman's 1834 review beats the pants off of sour old Alexander Campbell's 1831 "Delusions" article, six ways to Sunday. Besides which, as Dr. Givens (and B. H. Roberts before him) perceptively realized, Rev. Campbell slowly evolved 2 in his published statements regarding the supposed authorship of the book. Once he realized he'd lost most of Sidney Rigdon's Campbellite parishioners for good, Rev. Alex came around to the Spalding-Rigdon explanations 3 for our first tome of latter day scripture. Fawn Brodie may have built an entire psycho-bio reputation by standing on the promises of Alex her mentor, but the good Reverend himself turned those 1831 "Smith alone" foundations to sand in his various subsequent pronouncements. Shame upon you, Alexander, for leading Sister Fawn astray from saintly Ogden and into the dens of apostasy with your baseless accusations! __________ 1 Had Joseph Smith, jr. understood copyright law just a little better in 1830, he probably would have not sent the Book of Mormon forth into the world with himself listed as "Author." However, this lapse in good judgment does not end with Joseph's lack of proper attention to the title page -- he also identifies himself as "The Author" at the end of his "Preface" (pp. iii-iv). That introduction accomplished little more than to "stir up the hearts of this generation, that they might not receive" his work as an honest effort. The self-serving "Preface" was dropped from LDS and RLDS editions of the book over a century ago. 2 If I must fault Matthew on any particular important point -- and I suppose that is my duty here, right? -- it would have to be for his failure to check out what several of his source-people had to say about Smith, Rigdon, Spalding, relevant texts, etc. later on in their information-giving careers. It's all good and well to tell the members down at the ward meeting house that Elder Benjamin Winchester said such-and-such on one fine day back in 1840; but if we really want to be honest about such things, we also need to admit that he (and several others) changed their tunes substantially as time went by, right? -- "Play it again, Ben." It certainly gets my attention when one of my LDS friends can quote Sister Emma Smith, chapter and verse, in her knowledgeable refutations of the Spalding-Rigdon claims. But I get just as attentive when one of my own co-religionists hands me certified Emma statements or excerpts from her long-suppressed diary, declaring that her husband never practiced polygamy. We all know that Emma lied about that no-polygamy stuff, so why should I (or anybody else) trust her too closely when she starts telling us about other parts of our mysterious Mormon past? Now, don't get me wrong, I'm not saying that Matthew B. Brown can't present Em's and Ben's testimony in his apologetics, that's a no-brainer. But, if he or any other Utah Elder decides to do that in order to demonstrate their polemical positions, I expect them to be honest enough with us all to clue us into the problematic side of their sources. FAIR enough? 3 The Rev. Alexander Campbell's public progression, from supporter of the "Smith alone" explanation to propounder of the Spalding-Rigdon explanation for Book of Mormon origins, is documented in the comments section accompanying excerpts from Dr. Terryl L. Givens' 2002 book, By the Hand of Mormon. |

|

Dale's Comments, Part 2:

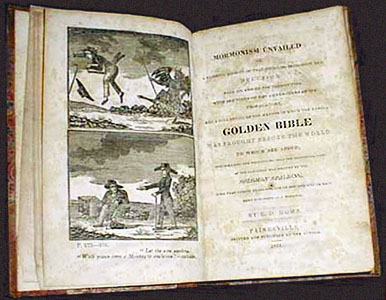

The Real Author of Mormonism Unvailed? Well, at least Matthew spelled the title correctly. Word has it that round about 1828 an eastern printer did a knock-off of Bill Morgan's exposé, renaming the filched booklet "Masonry Unvailed" to hide the dirty deed. Anti-Masonic newspaper editor Eber Dudley Howe liked the catchy title so much that he kept the second half of it for Esek Rosa's 1834 book --- oops, I'm getting ahead of myself here! Bro. Matthew tells us that "in 1834 a new theory for the origin of the Book of Mormon was proposed by a man named Philastus Hurlbut." Now, what about that! They say that "close" counts in horseshoes, but I'm not sure that Matthew quite deserves a chalk mark on his side of the blackboard for this precarious pitch. He makes it sound like Hurlbut was some egghead theorist, contemplating hypothetical ways in which acrimonious anti-Mormons could account for the coming forth of the Book of Mormon without having to make any reference to the God of Israel. Matthew's pitch comes across about as well as my saying that I want to eat a cake, so I'll go out and invent sugar, flour and eggs in order to cook one up. However, since Matthew has here neatly side-stepped the entire problem of the troublesome "Conneaut witnesses," 1 I'll follow his lead and just talk about D. P. Hurlbut for a little while. We can begin by looking at his Dec. 20, 1833 press release: Doct. P. Hurlbert [sic], of Kirtland, Ohio... requests us to say, that he has succeeded in accomplishing the object of his mission, and that an authentic history of the whole affair will shortly be given to the public. The original manuscript of the Book [of Mormon] was written some thirty years since, by a respectable clergyman... The pretended religious character of the work has been superadded by some more modern hand -- believed to be the notorious Rigdon. These particulars have been derived by Dr. Hurlbert from the widow of the author of the original manuscript.So, it looks like we'll need to move the date of Hurlbut's supposed theorizing back to late 1833, at the very least. But, at this point, we need to ask Matthew, where exactly is the "theory" in all of this? The man says that "the widow" of "a respectable clergyman" told him that her late husband wrote the "original manuscript" for what became the Book of Mormon, and that she accused "the notorious Rigdon" of gaining access to that old story and adding to it some "religious character." Again I ask, where is the "theory" here? The only hypothesis I can see is the necessary guess that "the notorious Rigdon" was the same Sidney Rigdon who lived within walking distance of downtown Pittsburgh from birth up to 1817, and then returned to live right in "the burgh" between 1822 and 1826. If Matthew were to accuse me of obtaining a copy of his Master's thesis, adding a few things to give it a somewhat different "character," and then publishing that text under my own name, he would not be stating some "theory" he was working through in his imagination; he would instead be bringing charges against me for what he would assert to be facts. The only "theory" involved is that Matthew might speculate that I obtained my copy of his thesis from my favorite library or some such place. Luckily for us, Spalding's widow and other members of their extended family provided additional details for these 1833 accusations, and we need not rely totally upon what Hurlbut was saying in the papers for information on the matter. That is to say, enough of what he asserts can be demonstrated from other sources that we need not theorize that Hurlbut made up this whole story out of his own imagination. But let's back up a few months in time and figure out how it was that D. P. Hurlbut ever got to the point of wanting to place such a press release in a Palmyra, New York newspaper. 2 D. P. Hurlbut's lawyer relates this account of things: In the winter of 1833-'34 several gentlemen in Willoughby, Painesville, and Mentor formed themselves into a committee to inquire into the origin of the Mormon Bible. Of the members of the committee in Willoughby were Judge Allen, Dr. and Samuel Wilson, Jonathon Lapham, and myself. The committee held several meetings at the house of Mr. Corning, in Mentor. The place is now owned by Mr. Garfield. They employed a man by the name of [Hurlbut], who was once a Mormon, to help in the investigation.Although the lawyer, James A. Briggs, Esq., says that the "committee" that "employed" D. P. Hurlbut to do some "investigation" was meeting during "the winter of 1833-'34," my inspection of the dates affixed to various statements and documents gathered by Hurlbut tells me that he was first employed by the "committee" during the summer of 1833 -- primarily to travel to the east and there conduct research on Mormon origins. Probably that "committee" had its beginnings a few months before Briggs began attending its meetings. It seems likely that committee members living in Willoughby first called Mr. Briggs in to act as Hurlbut's lawyer, after the ex-Mormon returned to Kirtland from New York, on or about Dec. 18, 1833. Dale W Adams, who has studied Hurlbut's chronology, gives us this opinion: "Possibly during July, 1833 Hurlbut met with a group of anti-Mormons in the Kirtland/Mentor area and proposed soliciting financial support to travel east to gather evidence against Joseph Smith. Based on his earlier talks with John Spalding, Hurlbut knew that Solomon Spalding's wife might have a manuscript that would confirm the Spalding Myth. The former Mrs. Spalding, Matilda Sabine, was then living in Monson, Massachusetts with her daughter and John undoubtedly gave Hurlbut directions for contacting her, or at least how to contact her brother who lived near Syracuse, New York."Having looked into this chronology a little myself, I am inclined to agree with Bro. Adams, that D. P. Hurlbut met with a northern Ohio anti-Mormon "committee" in mid 1833 and presented to its members the rudiments of the Spalding authorship claims (probably without yet including the allegation that Sidney Rigdon edited Spalding's writings). He got financing from some of these anti-Mormons (including a few of the same men named by James A. Briggs) to chase down the damning evidence, and the rest, as they say, is history. At the risk of my beginning to sound repetitious, I say again that D. P. Hurlbut originated no "theory" at this point in time. If somebody had then told him that Joe Smith's dog was named Fido, and Hurlbut had reported that information, he would not have been "theorizing" about Smith's dog -- just passing along a purported eye-witness claim. Despite what some defenders of the Mormon point of view have sometimes said, Mr. Hurlbut got his pocketful of Spalding claims, fair and square, from folks who had known Spalding; from folks who had been saying essentially the same things Hurlbut reportedly relayed to the ant-Mormon committee and later summarized in that Palmyra press release. No "theory" here yet -- just eye-witness claims. Let's Make a Theory Now, it might reasonably be argued that when D. P. Hurlbut first added Sidney Rigdon's name to the original 1832-33 Spalding authorship claims, and published that amended allegation in the 1833 press release, that then and there he came up with a "theory" all of his own. After all, none of the "Conneaut witnesses" mention Sidney Rigdon, not even in the two supplementary statements (given by Aaron Wright and by John Spalding) not published by Howe. So, if the "Conneaut witnesses" didn't mention Rigdon, then the addition of his name to their accusations is a theoretical augmentation, right? I conceded this point to Dr. Givens when I reviewed his book, but only on technical grounds. That is, only if it was indeed D. P. Hurlbut who first attached Rigdon's name to the claims he brought before the anti-Mormon committee in mid 1833. At that point -- if he did such a thing -- the original Spalding authorship claims might have been transformed into the Spalding-Rigdon authorship "theory." However, that much admitted, I am not at all convinced that it was D. P. Hurlbut who first attached Rigdon's name to the authorship assertions and thus originated any such "theory" -- rather, I think it is very likely (as he himself declares in his press release) that he got the whole story: Nephites, manuscripts, Rigdon, et al. from Spalding's widow, when he went to visit her in Monson, Massachusetts during the late fall of 1833. I say this because the widow and other members of the extended Spalding family independently and early on associated Sidney Rigdon's name with the fate of the manuscript(s) of Solomon Spalding. 3 Matthew has not taken the trouble to cite that set of eye-witness evidence, so I'll not launch into an extended treatise on that issue, for the time being. As to when the actual "theorizing" began -- I'll admit that in the hands of Hurlbut and Howe the widow's 1833 accusations (that a young Sidney Rigdon played around with the text of her late husband's writings) became the 1834 "Spalding-Rigdon theory," after a few more bells and whistles got added on. That's why I'm willing to grant Matthew a "close" decision when he says that "in 1834 a new theory for the origin of the Book of Mormon was proposed by a man named Philastus Hurlbut." The trouble with Matthew's reconstruction of things is that it leaves out what happened in 1832-33. To my way of thinking we can't simply jump into the first part of the year 1834 and make it look like D. P. Hurlbut snatched his explanations out of thin air. I think it is very important that we do not lose sight of the fact that Solomon Spalding's old neighbors and family members did not give out their concerned accusations under the title of "theory." However, that much stated, I think that Howe truly was dependent upon Hurlbut for most of the elements he (Howe) articulated in his 1834 explanation on where the Book of Mormon came from. Whether or not D. P. Hurlbut was fully truthful with Mr. Howe is another question altogether. But probably Hurlbut can marginally be credited with supplying more to the 1834 theory than Howe did. To put it another way, Howe's book contains a couple of speculative details not voiced in any known statements provided by Spalding's associates and family. Whether or not D. P. Hurlbut propounded those same additional details in the lectures he conducted in and around Kirtland prior to his arrest at the beginning of January, 1834, I do not know. I firmly believe that the most we can say is that the Spalding-Rigdon "theory" was first published in November, 1834 when Howe issued his book and that, even then, practically the totality of that "theory" is comprised of assertions (not imaginative guesses) first voiced by Spalding's widow and other concerned persons during 1832-33. 4 If those assertions were all (or mostly all) fallacious, then perhaps Matthew and I could start reading from the same historical page from here on out. But he has not addressed the credibility of the old witnesses' testimony, so I'll not get into that stuff either, just yet. Clapp, Rosa, and Who? Now, on to that other interesting authorship question -- for $64, tell me who wrote Mormonism Unvailed. What, no takers? OK, I'll elucidate that obscure mystery for the reading pleasure of Matthew and others interested in such oddities. According to the Rev. Clark Braden, speaking in 1891, the answer is: "Dr. Roser wrote a history; Booth wrote his experience among the Mormons; Clapp made a criticism; Howe made the book, and three thousand of them were scattered all around." As I've pointed out in my review of Ronald W. Walker's recent book, the "Dr. Roser" referred to by Braden was Dr. Storm Rosa of Painesville, but probably his brother, Esek H. Rosa (1807-1882), an accountant in the same town, did most of the book's editing. Several presumably reliable old sources invoke Esek Rosa's name 5 as the book's main editor and I'm convinced that identification is the correct one. The input from the Campbellite Elder, Matthew S. Clapp of Mentor, consisted of little more than an expansion of his Feb., 1831 contribution, as first published in Howe's Painesville Telegraph. The reprints of Ezra Booth's 1831 letters, the addition of Father Isaac Hale's 1834 letter, and the insertion of other interesting bits and pieces of information into the 1834 text can mostly be credited to hands other than Hurlbut's. He is responsible for most of the statements (or affidavits), a few allegations concerning Spalding's widow and some folks in Pittsburgh, and very little else, I'd guess. The sum total of new (previously unpublished) material in Mormonism Unvailed cannot be more than two or three chapters worth of its entire text. Probably E. D. Howe wrote less than a dozen pages in the book that bears his name. __________ 1 The eight witnesses whose statements are published on pp. 278-86 of Howe's 1834 book are: John Spalding (Solomon's brother), Martha Spalding (Solomon's sister-in-law), Henry Lake (his business partner in a mill and forge), John N. Miller (his employee), Aaron Wright (his fellow mill operator), Oliver Smith (his friend), Nahum Howard (his friend and doctor), and Artemas Cunningham (one of his creditors). These eight "Conneaut witnesses" all lived, at one time or another, near the banks of Conneaut Creek, which crosses the Ohio-Pennsylvania border just south of the Lake Erie shore and empties into the lake at what is now Conneaut, Ohio. Two of the eight witnesses supplied additional testimony not published in the 1834 book. To this basic list of eight deponents might be added the following additional witnesses, who also left statements claiming to have had interactions with Solomon Spalding and to have known something about his writings: Matilda Spalding Davison (Solomon's widow), Matilda Spalding McKinstry (their foster daughter), Josiah Spalding (his brother), Lyman Jackson (his friend), Abner Jackson (son of his friend), William Leffingwell (his proor-reader), Daniel Spalding (his nephew), Dan M. Spencer (a visitor), Robert Harper (a visitor), Erastus Rudd (son of his friend), Nehemiah King (his surveyor and doctor), Robert Campbell (a visitor), and Robert Patterson, Sr. (his choice as a publisher). In addition to all of these, there are a number of persons who claimed to know something about the activities of one or more of the above witnesses, people who claimed to know something about D. P. Hurlbut or E. D. Howe, and people whose questionable claims to have known something about Spalding's writings cannot be well verified. 2 The timing of Hurlbut's press release, in the Dec. 20, 1833 issue of the Palmyra Wayne Sentinel, is best understood in the context of dates appearing on the various statements he solicited in the Palmyra area between the beginning of November and the middle of December. Assuming that the dates affixed to these statements (as published by E. D. Howe) are the correct ones, Hurlbut was absent from the Palmyra area between Nov. 16th and Nov. 27th (when he evidently traveled to eastern New York and Massachussetts) and then he returned to take more statements in and around Palmyra between Nov. 27th and Dec. 13th. On Dec. 6, 1833 the Wayne Sentinel published an article which mentioned that Hurlbut was in the area "in behalf of the people of Kirtland for the purpose of investigating the origin of the Mormon sect." He probably left New York on his return to Kirtland a few days before his Dec. 20, 1833 press release appeared in that same paper. 3 Spalding's widow was quoted in 1839 as saying: "Sidney Rigdon, who has figured so largely in the history of the Mormons, was at this time [c. 1812-16] connected with the printing office of Mr. Patterson, as is well known in that region, and as Rigdon himself has frequently stated. Here he had ample opportunity to become acquainted with Mr. Spaulding's manuscript and to copy it if he chose. It was a matter of notoriety and interest to all who were connected with the printing establishment." There is one extraneous error that has slipped into this quotation -- that Rigdon frequently stated he was connected with a Pittsburgh print-shop. What was reported of Rigdon, in Howe's 1834 book, is that "about the year 1823 or '24... Sidney Rigdon located himself in that city [Pittsburgh]. We have been credibly informed that he was on terms of intimacy with Lambdin, being seen frequently in his shop. Rigdon resided in Pittsburgh about three years, and during the whole of that time, as he has since frequently asserted, abandoned preaching and all other employment, for the purpose of studying the bible." As for Rigdon being a printer or a print-shop employee, there is no evidence for that statement. Elizabeth Haven reported in 1843 that Rigdon informed her that "He studied for the ministry in his youth, then was employed in a newspaper office." This journalistic employment might have been anywhere (including for the Mormons) following his ministerial studies, but that was evidently after Spalding died. The stronger possible "connection" of Rigdon to Pittsburgh printers and publishers would have been in his role as a tanner and currier (a preparer of leather for book-bindings, etc.). Rigdon himself admits to working "in the humble capacity of a journeyman tanner" in Pittsburgh after mid 1823. He engaged in this humble leather-working occupation in partnership with his wife's brother -- their establishment closed on Sept. 25, 1825. Following closure of "the old stand" on Penn Street, Sidney Rigdon was relieved of his guardianship of a child, David Ferguson, by the local court. This happened on Nov. 11, 1825, freeing Sidney to move his family out of Allegheny County. Rigdon nowhere reveals where and when he served the apprenticeship necessary for his becoming a journeyman -- presumably he completed that training near his home, just south of Pittsburgh, before he began his studies for the ministry with the Baptist Rev. Andrew Clark at North Sewickley, Beaver County, Pennsylvania, during the fall of 1818. Sidney may have served his apprenticeship on a part-time basis, working mostly during the winter months, when his obligation to labor on his parents' farm was not so demanding. There were then several tanneries located within walking distance of his home, south of Pittsburgh. An example of a later advertisement for such a tannery was published in the Nov. 20, 1822 issue of the Pittsburgh Mercury by Thomas M. Henry, who was seeking "an apprentice" between "sixteen to seventeen years of age" to help him in his "tanning and currying." Mr. Henry's business was located in St. Clair township, Allegheny Co., very near Rigdon's home. Postulating Rigdon's own tanning apprenticeship to have begun at about this same age, he may have been working in the "tanning and currying" trade as early as 1810. Working only seasonally (when he could break away from farm-work), Rigdon might have taken 4 to 5 years to finish his apprenticeship and earn journeyman's status. In the meanwhile (1810-1815?) it is not unreasonable to supposed that young Sidney was employed by his master to occasionally take "curried leather" into nearby Pittsburgh, for sale to the Patterson book-bindery. See the Aug. 10, 1814 ad of Robert and Joseph Patterson, for some idea of when and how they operated their bindery and sub-contracted labor for other regional binderies. See also the Oct. 14, 1882 letter of Isaac Craig for a reference to Rigdon's c. 1823-26 "tannery on Penn street" where he made "book-binders sheep-skins," by the sale of which he came into connection "with Engles," a printer and co-worker with J. Harrison Lambdin. See also the 1879 recollection of a Pittsburgh old-timer who recalled "Sidney Rigdon, tanner and currier" who ran a "shop on Penn street," where it is "likely that, in the business transactions between book-binder [Robert Patterson, employer of Lambdin] and tanner, Sidney Rigdon took the Spaulding manuscript." For confirmation of Rigdon's occupation as a local tanner and his occasional presence in Pittsburgh, in the company of J. H. Lambdin, see Rebecca J. Eichbaum's statement of Sept. 18, 1879 and the Pittsburgh Commonwealth letter-lists for July 9, 1816 and other dates of that period. 4 Another interesting source (from outside the Spalding-Sabine extended family) is the 1880 statement of Ann Treadwell Redfield, who says she was the "principal of the Onondaga Valley Academy," on the outskirts of what is now Syracuse, "in the year 1818." At that time this lady headmaster "resided in the house of William H. Sabine, Esq.," the brother of Spalding's widow. The widow and her foster daughter were then also living in the same house. According to Redfield, she recalled "the family talk of a manuscript" then in the possession of "Mr. Sabine's sister... which her husband, the Rev. Mr. Spaulding, had written somewhere in the West.... I remember also to have heard Mr. Sabine talk of the romance... Mrs. Spaulding believed that Sidney Rigdon had copied the manuscript while it was in Patterson's printing office, in Pittsburgh. She spoke of it with regret. I never saw her after her marriage to Mr. Davison of Hartwick." If Spalding's widow was speaking of Sidney Rigdon's involvement with the "Manuscript Found" as early as 1818, that is somewhat remarkable, as Rigdon was then practically unknown outside of Pittsburgh and the Baptist congregations of that region. However, in Josiah Spalding's 1855 testimony, he says that his sister-in-law, the widow, "informed me that soon after they [the Spalding couple] arrived at Pittsburg a man followed them, I do not recollect his name, but he was afterwards known to be a leading Mormon. He got into the employment of a printer, and he told the printer about my brother's composition." Exactly who this "man" was, Josiah Spalding does not say, nor does he make it very clear, from whence and to whence, the unnamed man "followed them." Perhaps all he means to say is that the widow recalled her husband being followed around, in the Pittsburgh area, by this "man" who "was afterwards known to be a leading Mormon," and that the man took a special interest in Solomon's writings. This sounds to me like yet another indication that Spalding's widow believed the young Sidney Rigdon was known to her husband and that she believed (at some point prior to 1834) that he had tried to inject himself into her husband's attempts at publishing the "Manuscript Found." Just how closely Solomon Spalding's wife monitored her husband's literary output and attempts at publishing his writings remains unclear. If what is related of her in E. D. Howe's book is to be believed, she was very detached from those activities. It seems more likely that, once their family moved to the hamlet of Amity in 1814, she would have not been in a position to know much about young Sidney Rigdon. It is more probable, however, that she would have been acquainted with the Rigdons who lived just down the street from the "temperance tavern" she and her husband managed in Amity. This was the family of Sidney's aunt, the widow Mary Rigdon and her children. Mary was living in Amity in 1810 (see the actual census report, but ignore the problematical index for Amwell township) but had departed by 1820. It is possible that Spalding's widow later confused one of these Rigdons with a Rigdon "afterwards known to be a leading Mormon," which could have included Sidney Rigdon, Sidney's mother, Sidney's brother Carvil Rigdon, later Patriarch of the church at Pittsburgh, etc. Ellen E. Dickinson, Spalding's great-niece, blows this old family tradition of the "man" who "followed" Solomon, out of all its original proportions by stating in her 1884 book: "A young printer named Sidney Rigdon, was in Mr. Patterson's printing house; he had been there but a short time, and, from many indisputable facts, it is believed he had followed Mr. Spaulding from Conneaut, or its immediate neighborhood, and having heard him read "The Manuscript Found," and announce his plans for its publication, devised a treachery toward both author and publisher, which the world has reason to remember. This same Sidney Rigdon figured prominently twenty years later as a preacher among the Mormons." Like so many of Mrs. Dickinson's imaginative interpretations of past events in her family, this account is totally ludicrous. Mrs. McKinstry's son John relayed an equally laughable and muddled account, in 1877 where he says: "Rev. Mr. Spaulding was prevailed upon to read his production to his neighbors as it progressed... Among the attentive listeners at these readings were Joe Smith and Sidney Rigdon, the same who founded Mormonism. Not only did Smith hear the manuscript read, but on one occasion, as Mrs. Davison frequently testified before her death, he borrowed it for a week or so." John provided a somewhat more believeable story when he said, in 1879: "the 'MS.' was not delivered in person to Hurlbut, but that Grandmother... gave Hurlbut a letter to this Mrs. Clark requesting her to deliver the 'MS.' to him... had the 'MS.' not been in said trunk, she, Grandmother never would have written that letter... she had let Hurlbut have the 'MS.' -- upon his solemn promise to return the same after it had been compared with the book of Mormon... It is altogether probable that the subject must have been referred to on Grandmothers meeting Mrs Clark again, and it is equally probable that she had no occasion to think that Mrs Clark failed to deliver the 'MS.' to Hurlbut." 5 Two of the more easily accessible sources crediting Esek or Storm Rosa with the editing of Howe's 1834 book are "Reply to Chicago Inter-Ocean" in the Feb. 15, 1877 issue of the Saints' Herald and K. A. Bell's statement in the Jan. 1888 issue of Naked Truths About Mormonism. |

|

Dale's Comments, Part 3:

Who Wrote Those "More History Parts"? Matthew next tells us, "This theory postulated that Joseph Smith was too illiterate to have produced the Book of Mormon by himself and therefore must have received some assistance." What can I say? None of us can go back to 1834 and ascertain what a "theory postulated," correct? I think Matthew knows this, and that is why he does not name a "postulator" for this notion of Smith's illiteracy. As I've already said, the local folks in and around Manchester and Palmyra already knew that much. So who was doing all this "postulating" of a known fact? All I can do is guess -- perhaps interested parties who lived at such a distance from Palmyra that they knew little or nothing about young Joe -- perhaps a handful of early 19th century religious figures like Alexander Campbell, La Roy Sunderland, and Origen Bacheler. But those people did not devise the original "theory," now did they? Sure, I suppose that now and then, in the smoke-filled editorial offices of New York City newspapers, there were a few wags with nothing better to do than cook up ways to persecute my Mormon ancestors at Kirtland, Far West and Nauvoo. But those journalists did not devise the original "theory" either. Let's not fool ourselves into thinking that is where the Spalding-Rigdon authorship claims came from, friends. Ain't so. Despite the fact that the likes of Hurlbut or Howe tacked on an explanation or two, now and then, the original authorship claims came from the friends, associates, and family members of Solomon Spalding himself. That much can and must be admitted. Scholarship and personal integrity demand as much, even if some of us do believe that the martyred Prophet Joseph, Jr. -- honored and blest be his ever-great name -- really does hold the keys to the dispensation of the fulness of times. No matter that, it's still OK to admit the truth -- doing just that much is not going to make the "latter day work" crumble to dust; honest Lamanite, it won't. But enough of my virtuous verbosity; let's get back to what Bro. Matthew was saying -- he tells us: "This theory claimed that Sidney Rigdon wrote the religious parts of the Book of Mormon while the historical parts were plagiarized from an unpublished manuscript written in 1812 by Solomon Spaulding -- Rigdon having secretly acquired the Spaulding document from a Pittsburgh printer named Jonathan H. Lambdin." Sounds like an interesting explanation to me. Now, just which parts of that explanation did not originate with Spalding's friends and family? I need to know that before I begin to conduct some useful research into this rhetorical relic of the Restoration. I mean, it's alright for a few of us Latter Day Saints to actually check out what Bro. Matthew has said here, isn't it? Well, I'm assuming that it is allowable, and so that's just what I intend to do. So then, which parts of the Spalding-Rigdon explanation did not originate with Solomon Spalding's family and acquaintances? Maybe it was the part that alleges Spalding wrote pseudo-historical stories in archaic English? Nope. We have too much documentation of that fact to cast it into the lake of fire. Well, maybe the part about his taking those writings to Pittsburgh in the fall of 1812? Nope again -- I think that part is also pretty well established. Maybe the part of the explanation that says Spalding's writings had "religious parts" and "historical parts" is a lie? Sorry, nope again. Just read the manuscript of his now on file at Oberlin College to see that he was prone to write such things. 1 Matthew says that the "theory claimed that Sidney Rigdon wrote the religious parts of the Book of Mormon," but that is less than half true. As I've documented elsewhere, 2 people who knew Rigdon or knew his checkered reputation, were accusing him of writing the book several months before the first Spalding authorship claims were first circulated. So Rigdon was a major "suspect" practically from the beginning. What happened is that Spalding's widow suspected Rigdon's surreptitious involvement since the days when they all lived in Pittsburgh (or on its outskirts) and she said as much to D. P. Hurlbut, who then publicized her suspicions in his Dec. 20, 1833 press release. The widow reiterated her suspicions in her Apr. 1, 1839 statement, and other people claiming to have personal knowledge of the matter added their corroboration as time passed. 3 Good scholarship tells us that both young Sid Rigdon and Solomon Spalding were in Pittsburgh at about the same time (at least often enough to pick up their mail) before Spalding died in 1816. True, Sidney had a couple of hours' walk into town, from the family farm, but on a lucky day he could catch a boat down the creek, ride the current of the river to "the point," and be in the "burgh" before lunch, with nary a bead of sweat on his youthful brow. Did he occassionally consort with printer J. Harrison Lambdin in Pittsburgh? Howe's book said he did -- the postal clerk in that iron city said he did -- and Rigdon never denied knowing Lambdin, whether in the days before 1817, when Sidney went off to his preacher's studies, or in the days after he was "busted" by the Baptists as a pernicious pastor, back in the "burgh" in 1823. Word has it that young Sidney learned the tanning trade and peddled leather book-covers to publishers like the Patterson brothers. 4 In his May 27, 1839 letter to the Quincy Whig, Rigdon specifically admits to knowing Robert Patterson, Sr. (the legal guardian, employer, and later business partner of J. Harrison Lambdin). Rigdon's co-pastor with the proto-Cambellite congregation in Pittsburgh, the Rev. Walter Scott, says: "That Rigdon was ever connected with the printing office of Mr. Patterson or that this gentleman ever possessed a printing office in Pittsburgh, is unknown to me, although I lived there, and also know Mr. Patterson very well, who is a bookseller. But Rigdon was a Baptist minister in Pittsburgh, and I knew him to be perfectly known to Mr. Robert Patterson." Rev. Scott speaks correctly: Robert Patterson, Sr. was a book-seller and occasional publisher who contracted his work out to his cousin, Silas Engles, who at one time employed J. Harrison Lambdin. Thus, the Patterson brothers, Robert and Joseph, had no printing office of their own. But Scott knew that Sidney Rigdon was "perfectly known to Mr. Robert Patterson." One more example, the Mormon Elder William Small visited Robert Patterson, Sr. at an early day and says Patterson told him: "that Sidney Rigdon was not connected with the office for several years [after]" Solomon Spalding died. Probably what Patterson was trying to say is that Rigdon never worked for him, or was directly connected with the book shop he and Lambdin operated, but that once their firm split up in Feb. 1823, that Rigdon had some direct connection with Lambdin's own short-lived book business. Finally, in 1842, Robert Patterson, Sr. signed a statement saying that "that a gentleman, from the East originally, had put into his hands a manuscript of a singular work, chiefly in the style of our English translation of the Bible." The publisher of this statement also says: "Mr. Patterson firmly believes also, from what he has heard of the Mormon Bible, that it is the same thing he examined at that time." The pamphlet in which these statements occur was published, advertised, and sold in Pittsburgh while Patterson was still living there -- he never denied that published testimony. When Matthew tells us that the "theory claimed that Sidney Rigdon... secretly acquired the Spaulding document from a Pittsburgh printer named Jonathan H. Lambdin," I ask, is he saying anything so terribly preposterous? Did Rigdon know and associate with Lambdin? Almost certainly he did. Was Rigdon "connected" with Lambdin's book business, in 1823-25, when Rigdon was a book-covering maker, operating a leather shop only a few blocks from Lambdin's office? Did Lambdin "inherit" a printer's copy of one of Spalding's unpublished manuscripts, after he and Patterson split up their business in 1823? Did Rigdon have access to such a document ("secretly" or otherwise) through Lambdin? I agree with Matthew, that at this point we are knee-deep in theorizing, but is it useless and delusional theorizing -- or, do all of these possible historical connections warrant a little further investigation? Is it OK if I person like myself investigates just a bit deeper into this matter? I hope so, because that is what I intend to do. Matthew tells us that "Hurlbut's theory asserts that, in order to create robust book sales, Lambdin "placed the 'Manuscript Found' of Spalding, in the hands of Rigdon, to be embellished, altered, and added to as he might think expedient." Is that so? Actually, Howe's book doesn't say that Lambdin gave his friend Rigdon Spalding's manuscript, to edit, "in order to create robust book sales." What is said there is that "Lambdin, after having failed in business, had recourse to the old manuscripts then in his possession, in order to raise the wind, by a book speculation." This does not necessarily mean that Lambdin intended to publish all the abandoned manuscripts that had fallen into his possession, or that he even had the funds to print up a few of them. I think that it means he was ready to make use of the unpublished texts in any way he could -- by selling them outright, extracting printable material from a few and selling that, or perhaps allowing a friend to embellish a couple of the cast-off stories and give him a cut of the profits if the polished-up stuff could be sold to a publisher. I wasn't there and I don't know, but by the time Howe's book got published, Lambdin wasn't around to spill the beans either way -- he was six feet under the Pittsburgh clay. Could have Lambdin possessed a copy of a Spalding story as late as Aug. 1, 1825, when he died and his book business ended for good? Yes, I suppose so. Could have Rigdon taken such a story -- perhaps a printers' copy he himself had penned for Silas Engles a decade earlier -- and "embellished" it? Again, I think that's entirely possible. Does that prove he turned Solomon Spalding's "Manuscript Found" into the Book of Mormon? Not at all. That, as Matthew says, is only a theory. The question is -- should such a theory be investigated any further, or should it be consigned to the dustbin of history and forgotten forthwith? At this point I'm inclined to agree with Bro. Matthew, that all this theorizing is leading us nowhere fast. The evidence is no doubt "disputed" (what evidence is not, when non-Mormons and Mormons sort through the same stacks for proof?) so I'll leave it alone for a while. __________ 1 In Solomon Spalding's Oberlin manuscript story, his fictional ancient Americans keep their religious records separate from their civil records -- which perhaps doesn't mean much in a fictional culture that was set up as a virtual theocracy, with heritary kingship and high-priestship retained by the same elite family. Those writers who assert that Solomon Spalding, the pious Calvinist (??), would have been incapable of concocting pseudo-scripture, ought to read his extracts from the "Sacred Roll" (not to be confused with the similarly named Shaker scriptures) as set down upon the pages of his Oberlin manuscript. On the other hand, don't expect the American Christians of 170 years ago to have acknowledged stuff like his fictional "Sacred Roll" to have been particularly "religious." In their narrow interpretation of things, even the rigid monotheism of Islam was in those days mistakenly termed "idolatrous," rather than truly "religious." Although Solomon Spalding reportedly wrote about ancient Israelites and cast his narrative in biblical English, several early witnesses affirm that they heard or saw a fictional history and not a purported revelation from God. Redick McKee, who had an opportunity of reading some of Spalding's later literary creations at Amity, described them as "what purported to be a veritable history of the nations or tribes who inhabited Canaan... His style was flowing and grammatical, though gaunt and abrupt -- very like the stories of the Maccabees and other apocryphal books, in the old bibles." It is easily seen how an early 19th century Christian might have read such a biblical-sounding story, and not thought of it as being "religious," unless it contained specific references to Christian theology and practices. On the other hand, it is not totally unimaginable to guess that the cynical Deist Solomon Spalding might have injected some subtle parodies of contemporary religion into one or more of his stories -- covering them over with ancient dates or foreign scenery, in much the same way Jonathan Swift clothed his satires of contemporary politics in similar thin disguises. The devout Presbyterian, Rev. Robert Patterson, sr., is unlikely to have ever published a book containing explicit parodies of Christianity, but he might have considered publishing a fictional history in which implicit jabs at camp-meeting religion or nascent Campbellism were disguised by a supposedly ancient setting. See Vernal Holley's Book of Mormon Authorship. pp. 23-34 for more on Spalding's probable contact with early Campbellism in Washington Co., Pennsylvania, c. 1812-1814. Holley remarks: "Washington, Pennsylvania, was the birthplace of [American] Campbellism in 1809... Amity was less than ten miles from Washington where Campbellism originated. Living in the area and being a trained minister, Spaulding would likely have had more than a casual interest in the recent revival activities and local news of the then evolving Campbellite movement... [and] would have been knowledgeable, and capable of incorporating interesting early Campbellite concepts into his sometimes satirical and subtly anti-religious writings." Holley adds this note: "Solomon Spalding may have spent the winter of 1813 or 1814 among the Campbellites of Washington, PA, see Gerald Langford's The Richard Harding Davis Years (NY, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1961), p. 4." Langford recounts the reminiscence of Rebecca Blaine Harding's mother Rachel Leet Wilson, who grew up in Washington, Pennsylvania. Langford says that: "Rachael... had been educated by her father's good friend Alexander Campbell, founder of the Disciples of Christ and that "her devout Baptist father threw open to all impoverished strangers, especially Baptist preachers down on their luck. One of these latter whom the girl [Rachel Leet Wilson] always remembered vividly, was a pale young Mr. Spalding, who while too ill to preach, spent a whole winter in her home writing a long story which he read aloud in the evenings. It was, according to Rebecca's later report, 'a fictitious story which Joseph Smith published afterwards as the Book of Mormon.'" Whether or not this old, twice-told recollection is an accurate one, it does demonstrate how Solomon Spalding could have encountered and reflected upon incipient Campbellism in or near Washington town, Washington Co., Pennsylvania, during his residence in that county. 2 See my Role of Sidney Rigdon comments section accompanying excerpts from Dr. Terryl L. Givens' 2002 book, By the Hand of Mormon, where I document some very early reports identifying Rigdon as the probable author of the Book of Mormon. When Ohio editor Warren Isham labeled that book "Campbellism Improved," in his Nov. 18, 1830 report he was implicitly saying much the same as was more clearly spelled out in the Cleveland Advertiser on Feb. 15, 1831, where Rigdon is portrayed as a maverick, knavish Campbellite attempting to "operate on his own capital" in the realm of religious doctrine. The article even suggesting that it was Rigdon's previous activities as a Campbellite preacher that led him "to test the validity of the doctrine contained in the Book of Mormon," not just as a basis for his own conversion, but as the work of a conniving baptizer, preparing proselytes to accept the same "restored" doctrines. These were the first known publications of what soon became a popular assumption -- that Rigdon had secretly contributed to the founding of the Mormon sect and the writing of its first scriptures. As the editor of the Advertiser puts it: "a noted mountebank by the name of Elder Rigdon" was "believed" by him and others to be the author of the Book of Mormon. Parley P. Pratt, one of Sidney's early, pre-Mormon, "Rigdonite" disciples, said in 1838 that "Early in 1831, Mr. Rigdon having been ordained, under our hands, visited elder J. Smith, Jr., in the state of New-York, for the first time; and from that time forth, rumor began to circulate, that he (Rigdon) was the author of the Book of Mormon." But probably the first specimens of this "rumor" were in circulation near Rigdon's Mentor-Kirtland "home base" even before he left to publicly visit with Seer Smith for the first time. Mormonism and Rigdon's special development of Campbellism were so much alike that some of those who knew the man and his preaching just naturally viewed the Book of Mormon as "Campbellism Improved." Several early writers on Mormonism developed the view that Sidney Rigdon had injected a great deal of unique "Rigdonite" religious tenets and practices into the new religion and its book. These views are summed up in 1914 by Charles A. Shook, who says: "The "Doctrine and Covenants" (34:2) throws out a hint of Rigdon's former connection with Mormonism in these words: "Behold, verily, verily I say unto my servant Sidney, I have looked upon thee and thy works... thou wast sent forth even as John, to prepare the way... and thou knew it not." Nearly all Gentiles will agree with the Mormons that Sidney prepared the way before the Mormon delusion, but when it comes to the statement that he knew it not, it is quite another thing." 3 Some of the more interesting accusations linking Rigdon with Solomon Spalding's writings came from one of his Amity, PA neighbors, Joseph Miller. The earliest Miller statements are probably lost to history; his first known testimony mentioning Solomon Spalding is from Mar. 26, 1869, where he briefly outlines his recollections. A more detailed statement was solicited from Miller ten years later, in which he says that Spalding "had left a transcript of the manuscript with Mr. Patterson, of Pittsburgh, Pa., for publication, that its publication was delayed until Mr. S. would write a preface, and in the mean time the transcript was spirited away and could not be found. Mr. S. told me that Sidney Rigdon had taken it, or that he was suspicioned for it. Recollect distinctly that Rigdon's name was used in that connection." Miller provided a couple of additional statements in which he said practically the same thing -- that a young Sidney Rigdon gained access to a "transcript" of Spalding's manuscript, while it was in the keeping of "Mr. Patterson of Pittsburgh." Miller neglects to say which "Mr. Patterson" this was, but his testimony sets the date for this incident before Spalding's death on Oct. 20, 1816. The firm of Robert and Joseph Patterson began operation in Pittsburgh about Nov. 5, 1812, and continued until Jan. 6, 1818, when it was reconstituted under the name of "R. Patterson & Lambdin." However, during the winter of 1814-15, Joseph's name disappeared from the from the firm's advertising and Robert probably took over most of its operations on his own. Since Robert Patterson says he employed (or contracted with) his cousin "Silas Engles" as the "general superintendent of the printing business... to him was entrusted the entire concerns of the office," and that he "supposed" that "Mr. Engles returned the manuscript" to Spalding, "after it had been some weeks," it would seem that any access Rigdon might have gained to Solomon Spalding's writings in Pittsburgh, during Spalding's lifetime, would have been through Mr. Engles (or through Engles' employees) and not directly from either of the Patterson brothers. Also, since practically all reports of this matter say that the "Manuscript Found" was eventually returned to Mr. Spalding, Rigdon (if he did gain access to the story during Spalding's lifetime) certainly did not steal the original "Manuscript Found." All that Spalding's widow says in this regard is that "Sidney Rigdon, who has figured so largely in the history of the Mormons, was at this time [c. 1812-16] connected with the printing office of Mr. Patterson... he had ample opportunity to become acquainted with Mr. Spaulding's manuscript and to copy it if he chose. It was a matter of notoriety and interest to all who were connected with the printing establishment." But, as has been demonstrated, the Patterson brothers did not operate Engles' "printing office" directly and they probably did not always know when Engles selected proffered manuscripts for editing and pre-publication work. No record remains saying whether or not Engles had a clean "printer's copy" of Spalding's manuscript written up, pending prepayment of its publication expenses. Finally, any formal "connection" between "tanner" Rigdon and "printer" Engles probably would have amounted to little more than the apprentice tanner occasionally dropping off some leather book-bindings, and reference to a formal "connection" (prior to Rigdon's opening his own leather shop in about 1823) remains speculative, requiring further investigation and documentation. The one piece of extant testimony (Eichbaum's statement) firmly placing Sidney in Engles' print-shop prior to Spalding's death does not claim any formal "connection" between Rigdon and Engles. So, once again, our attempts to reconstruct the slender supply of "facts" at this point have already turned to theorizing. My suggestion is that this purported early "connection" should be investigated more closely, through the application of our careful research and scholarship. 4 Besides operating a paper mill, a book bindery, and a book sales office, all in Pittsburgh, the Patterson Brothers did some occasional publishing, evidently making use of the printing press of their cousin, Silas Engles for most of that work. It seems likely that Joseph Patterson was the brother who supplied most of the capital to the firm. Mrs. Matilda S. McKinstry, the foster daughter of Solomon Spalding, provides practically the only known glimpse into the operations of the Pattersons, in a reminiscence she shared with her friend Redick McKee, in 1882 of "remembering to have heard her mother say that, before they left Pittsburgh, she accompanied her husband to the store of Mr. Patterson and heard a conversation in relation to the publication of the 'Manuscript.' There were two Mr. Pattersons present, one... had read several chapters of the 'Manuscript' and was struck favorably with its curious descriptions and its likeness to the ancient style of the Old Testament Scriptures. He thought it would be well to publish it, as it would attract attention and meet with a ready sale. He suggested, however, that Mr. Spaulding should write a brief preface" etc." The girl's own recollection of the Patterson's book-shop (which she calls a library) was more or less a vague one. She said in 1880: "I distinctly recollect visiting a library with my father which my mother told me was `Mr Patterson's;" the building was a large one, and over the door was a bust of what seemed to me at that time, as a beautiful lady, & impressed my childish fancy. I distinctly remember seeing in a chair in the center of the room, a large, heavy built man of florid complexion There was an other person in the room, and my father had a long conversation with him." In a recollection of Redick McKee, dated Jan. 25, 1886, Mr. McKee contributes some additional details: "Mr. Spaulding told me that at Pittsburg he became acquainted with the Rev. Robert Patterson who... thought favorably of the printing [of his story], but his manager of the publishing department -- a Mr. Engles or English -- had doubts... and thought the author should... pay the expenses... and the manuscript was laid aside in the office... Mr. Spaulding told me that while at Pittsburg he frequently met a young man named Sidney Rigdon at Mr. Patterson's bookstore and printing-office... He had read parts of the manuscript... [then] the manuscript could not then be found... This excited Mr. Spaulding's suspicions that Rigdon had taken it home. In a week or two it was found... The circumstance of this finding increased Mr. S.'s suspicions that Rigdon had taken the manuscript and made a copy of it." While this elaboration upon past events generally agrees with the assertions of Joseph Miller and Spalding's widow, McKee's allegations cannot be conclusively confirmed. However, in a letter written on Jan. 2, 1880, Spalding's foster daughter tells her cousin, Mrs. Ellen E. Dickinson, "While my father resided at Pittsburg the Manuscript was borrowed by one Patterson who owned a large book establishment and printing office. Sidney Rigdon was at that time [c. 1812-16] employed at this office and we have always believed that he copied it then and there." |

|

Dale's Comments, Part 4: