Tannerism - Reality or Shadow?

A Critical Review of

of the Tanners'

Did Spalding Write

The Book of

Mormon?

Salt Lake City,

Modern Microfilm Co., 1977

by: Dale R. Broadhurst

|

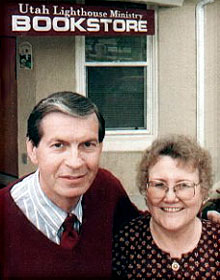

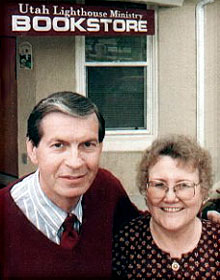

Associated Press wirephoto:

Associated Press wirephoto:

"Jerald and Sandra Tanner"

|

read part one of the Tanners' 1977 Spalding book

Mr. & Mrs. Tanner, Mormon Origins

& Solomon Spalding

Note: I placed an earlier version of this review at the old Spalding Studies site late in 1998, but for various reasons

it was transferred to SidneyRigdon.com early the following year. That first version was entitled "Tannerism: Reality or

Illusion." I removed it from the web shortly after updating its contents in Nov., 1999. Despite my bringing the review

to the attention of Mr. and Mrs. Tanner on several different occasions, my impression is that they never took the trouble

to read it. Some of their friends and supporters did read that earlier version, however, and a couple of those readers

advised me to re-write the text and remove some language they considered offensive to the Tanners (such as my

thoughtlessly saying, "I am more convinced than ever

that the Tanners effectively function as a mouthpiece for certain high-level parties within the LDS Church," when I meant

to say "mid-level"). Having hopefully now accomplished that task, I am (on April 6, 2001) returning my review to the web

and finally (on May 17, 2006) getting around to repairing broken links and such.

01. Place of the Tanners in Modern Mormon Studies

Anti-Mormon activists Jerald and Sandra Tanner have long been committed

to issuing a seemingly endless stream of published corrections and refutations of the practices, doctrines, policies,

and teachings of the LDS Church. Operating from their office, across from the Ball Park on Salt Lake City's West Temple

Street, they have continually researched the "errors" of Mormonism and offered their implicit suggestion that the LDS

members would be better off to leave the ranks of the Church, (as the Tanners themselves did over four decades ago).

Oddly enough, the Tanners, like myself, owe more than a little of their restoration skeptics' heritage to the late

James Wardle: RLDS athlete and barber, Mormon history buff,

and lifelong burr under the saddle blanket of the LDS hierarchy in Salt Lake City. Coming as we do, from a somewhat

similar mid-20th century Rocky Mountain background and a memorable early Latter Day Saint ancestry, it is interesting to

see that they and I have ended up on totally opposite sides of the religious fence today. Even so, I bear no animosity

toward them, simply for their having deserted the "latter day work" and turned against a people and a spiritual movement

I continue to find worthy of some approbation (despite my own

desertion). I do not at all discount the contributions

the Tanners have made to modern Mormon studies; in fact, I owe them a small debt of thanks, for selling me my first

copy of Eber D. Howe's infamous book many years ago. And

yet, even considering my generally favorable feelings toward the Tanners personally, I have long felt they were fighting

the wrong battles with "Mormonism" -- for the mistaken purposes -- and in the process lamentably misdirecting their

considerable talents and resources.

They (Sandra at least -- Jerald no longer enters the fray) are still the bug-bears of the Mormon Establishment at the

beginning of the 21st century. The day has long passed when copies of Fawn Brodie's book were banned from all LDS

meeting-house libraries -- but possession of the Tanners' Mormonism -- Shadow or Reality? remains an offense

requiring careful explanation for Mormons applying for Temple recommends. Despite their efforts to refute Mormonism, the

LDS Church leadership has long since learned to live with the pesky pair, generally ignoring what they have to say, and

continuing to grow world-wide at a remarkable pace. In their own, unintended way, this couple have become an institution

within an institution -- the accommodated "Goldstein underground" in a modern Mormon "1984." It is not unusual to see

Mormon apologists of the FAIR-FARMS-SHIELDS ilk buttressing their defensive essays with statements like, "Even the

Tanners agree that..." or "The Tanners argue that..." A strange illusion has grown up over the years on the fringes of

Mormondom -- a mind-set which believes that the Tanners criticize the Church; the Church's faithful then refute the

Tanners; and in the process all important controversies in Mormonism are addressed and settled one way or another. The

time is ripe to break that strange illusion.

02. The Period Context for "Did Spalding Write the Book of Mormon?"

A number of years ago I had the opportunity to attend a weekend Mormon historians' conclave held at Graceland College in

Lamoni, Iowa. There, in the showers of a Mens Room hung thick with Utah "chapel-chaps," I overheard one of the late

Leonard Arrington's cronies remarking that perhaps the Tanners "ought to be put on the payroll," in light of their

efforts to defend the Church's point of view. This remarkable witticism exchanged among showering members of the LDS

Historian's staff can only be comprehended in the context of one's having read the Tanners'

1977 publication: Did Spalding Write the Book of Mormon?

This odd book is comprised of five sections: "Part 1: Did Spalding Write the Book of Mormon?"; "Part 2: A Photomechanical

Reprint of Solomon Spalding's Manuscript Story, 1910 Edition"; "Part 3: Joseph Smith's Strange Account of the

First Vision"; "Part 4: 'The Book of Mormon,' A Chapter From the Book Mormonism -- Shadow or Reality?"; and,

"Part 5: Parallels Between the Book of Mormon and View of the Hebrews, by the Mormon Historian B. H. Roberts."

As the last four parts of their work appear to be attached primarily as appendices to the lead article, I'll concentrate

my comments on "Part 1: Did Spalding Write the Book of Mormon?" and pass by the other four sections with only an

occasional remark.

Part 1 of the 1977 Tanners' book was written during a strange time among a lengthy list of strange times, in the final

dispensation of the Latter Day Saints. The late 1970's were the days when men still decked themselves out in polyester

leisure suits; women were still unashamed to wear beehive hairdos (at least so in the Beehive State); the fire hydrants

were yet sporting red, white and blue paint from the US bi-centennial celebration; and Christian book stores were opening

their doors even in such unlikely places as Orem, Utah and Ammon, Idaho. Among the slick paper cover fundamentalist and

evangelical Christian offerings of those days -- over in the "cults section" -- the bookshop browser was sure to come

across titles like "Dr." Walter Martin's Kingdom of the Cults and Maze of Mormonism, along with Howard

Davis and associates' little book,

Who Really Wrote the Book of Mormon? and the pamphlets on how to witness to the deluded Mormon cultists.

These 1970s anti-Mormon mania books all offered the same basic message: the Saints' Book of Mormon was fraud cooked up

by Joseph Smith and "true" Christians were wise to avoid it altogether. What was remarkable about many such publications

of the period was their assertion that Smith had been so stupid as to steal his fraudulent scriptural passages

directly from the manuscript of failed novelist Solomon Spalding -- and that Smith exhibited even greater stupidity by

inserting Spalding's old handwritten pages straight into his own production, (specifically, the material now comprised

by I Nephi 4:20 to I Nephi 12:08 of the current LDS edition of the Book of Mormon).

The Tanners' own Shadow or Reality? would eventually receive national distribution in many of those same Christian

bookshops and take its rightful place alongside the aforementioned books on latter day cultism. But back in 1977 or 1978

the hopeful student of Tannerism would have been limited to the back room haunts of Salt Lake City's Zion's Books, The

Cosmic Areoplane, or the Tanners' own Modern Microfilm sales office, in his quest to peruse their newly minted

Did Spalding Write the Book of Mormon? This was a volume not especially dear to the anti-Mormon heart, for the

simple reason that, in its opening pages, Jerald and Sandra came out against the anti-cult-book claims that Smith had

been fool enough to insert 12 Spalding sheets into his "Dictated Manuscript" for the Book of Mormon. The 12 pages claim

appeared to be an open and shut case to the naive readers of the Martin and Davis books. Spalding's handwriting had been

"positively identified" on pirated photocopies of those 12 pages, though the original sheets themselves remained "hid up"

in the Archives of the LDS Church. Three of the world's foremost handwriting experts had uniformly agreed to this

remarkable "fact" and their names were splattered across numerous newspaper articles sent round the world. Thus, the

Mormon Church was proven to be utterly false and nothing more need be said about the matter. Or, was there something

fundamentally wrong with this rose hued scenerio?

03. The Message of "Did Spalding Write the Book of Mormon?"

The Tanners begin their five-part volume by quoting the June 25, 1977 Los Angeles Times article that had

originally kicked off the whole "12 pages" media feeding frenzy. From the content of that article it indeed appears

that California "researchers" Howard A. Davis, Wayne L. Cowdrey and Donald R. Scales had found handwriting experts

happy to publicly confirm the researchers' contention regarding the 12 Book of Mormon manuscript pages having been

written in Spalding's hand. However, in the next several paragraphs of their volume, the Tanners patiently and

methodically refuted practically every claim made in the Times article, and then went on to demonstrate how

the previously unidentified scribe of the 12 pages in question was almost certainly the same Smith scribe who wrote

out one of the Mormon leader's 1831 "revelations."

Jerald Tanner's personal account (pp. 4-5) of the events of those days is especially interesting:

STATEMENT BY JERALD TANNER, [ extracts, --

view full text ]

In our book Mormonism -- Shadow or Reality? page 166, we printed a photograph of the top of a page of the

original Book of Mormon manuscript... one of the California researchers was reading Mormonism -- Shadow or

Reality? when he ran into this photograph of the manuscript of the Book of Mormon. He had previously been examining

the handwriting of Solomon Spalding... and was struck with the fact that there was a resemblance between the two

writings. Subsequently three handwriting experts were consulted and are reported to have given support to this theory.

Several months before the discovery was announced a friend of the Spalding researchers came to Sandra and I with the

startling announcement that the source of the Book of Mormon had definitely been found... I noticed, however, that there

were dissimilarities between the two documents. For example, the manuscript written by Spalding uses capital letters

where proper names are given, whereas the writer of the Book of Mormon manuscript seems to omit this in most cases. We

have "nephi "jerusalem," and etc. Another dissimilarity is that Spalding usually uses the ampersand (&) instead of

writing out the word "and." In the Book of Mormon, however, it is usually written out. Sandra pointed out that some of

the similarities between the documents could be explained as peculiarities of the time period in which the documents

were produced... we cautioned this friend of the researchers that they should be very cautious in putting forth such a

sensational claim. Since it was such a secret matter, none of the documents were left with us for further inspection.

From our brief examination of the documents, however, we had some grave doubts about the whole thing.

After the discovery was announced... I received a phone call from a friend of the California researchers. He said that

Mr. William Kaye, a hand-writing expert from Los Angeles had been sent to examine the original Book of Mormon pages in

the Church archives, and he wondered if I would accompany Mr. Kaye to be sure that he was shown the right documents...

...As I was driving Mr. Kaye to Mormon headquarters, however, I became impressed with the fact that I should go in with

him. I had heard that the Church had a revelation, dated June, 1831, which contained

hand-writing which resembled that

found in the 12 contested pages of the Book of Mormon manuscript, I thought that this was a very important matter, and

I felt that I might be able to talk Church officials into showing Mr. Kaye this document.

After we parked the car... I mustered up my courage and proceeded with Mr. Kaye to the Church archives. I followed

behind Mr. Kaye as he was directed from one office to another and finally to the conference room. I sat down close to

him so that I would be able to have a good look at the documents. We were alone in the room for a few minutes, but then

Donald Schmidt, Church Archivist, entered with a cart containing a large number of documents... Dean Jessee and Don

LeFevre then entered the room, and I was introduced by my full name.

...as Mr. Kaye and myself continued to examine the documents we were treated with courtesy, I began to note and

discuss the important dissimilarities between the photocopies of the Spalding manuscript and the writing in the Book

of Mormon manuscript. Then the final blow came to the California researchers' theory. This was the revelation dated

June, 1831, Section 56 of the Doctrine and Covenants. The Church voluntarily produced this revelation and invited

Mr. Kaye to inspect it. The claim has been made that Mr. Kaye did not see the original of this revelation. I am

absolutely certain this is incorrect. Both the original revelation and a photocopy were given to us for inspection. I

noted the date at the top and the fact that the paper appeared to be very old. After looking carefully at the revelation,

I became convinced that it was probably written by the same scribe who wrote the 12 contested pages in the Book of Mormon

manuscript. Both manuscripts in turn differed from Spalding's work in important features.

I felt that the evidence furnished by the revelation was so devastating that I immediately went to the press with a

statement hoping that the whole matter could be resolved before more damage was done.

Jerald Tanner [signature]

Following this statement, the Tanners provide some information on how another of the California researchers' hired

handwriting experts, Henry Silver, withdrew from the affair at about the same time that expert William Kaye was delaying

offering any final decision on the handwriting. As it worked out at the time, the California researchers' third expert,

Howard Doulder, also soon withdrew from the investigation. By September 24th Doulder was telling the Times that

the Spalding MS and the questioned 12 pages had been written by "different authors." When Howard Davis and friends' book

Who Really Wrote the Book of Mormon? appeared in late 1977, the California researchers were forced to admit that

Doulder was saying "Solomon Spalding is NOT the author of the unidentified pages." Thus, in the end, two of the experts

never provided the California researchers with positive final reports and the third expert (William Kaye) only issued

an opinion (not a detailed report) on September 8th, that Spalding was the writer of the 12 pages. The Tanners' initial

premonition against this conclusion and their "grave doubts" on the whole matter, prior to the examination of the

documents, appear to have been well founded and were confirmed by their own conclusion "that the discovery would not

stand up under rigorous examination."

The June 1831 "Unknown Scribe" Document

(from the Tanners' 1977 book)

04. Further Considerations

The remainder of the Tanners' Part 1 consists of their presentation of evidence that Spalding did not physically write

the Book of Mormon manuscript pages preserved by the LDS Church, and so his name need not be called upon for an

explanation of why the Nephite narrative can be considered a 19th century production. In support of this first contention

the anti-Mormon couple present a number of convincing dissimilarities between the penmanship in Spalding's writing

and that found on the 12 pages perserved in the LDS Archives. Although Spalding and the unknown Mormon scribe of 1831

share a few similarities of penmanship (in a longhand style generally used in early 19th century America), such expected

similarities fade significantly, in light of evidence showing the many consistently different handwriting traits

that can be easily spotted by anybody who inspects the two documents.

This thoughtful presentation is followed with the Tanners' discussion of the fact that the 12 pages are written on the

same paper stock, with the same kind of ink, and in the same general manner as the known scribes' pages positioned both

before and after the questioned 12 pages. In addition to this, it should be pointed out that the 12 pages in question are

but a portion of several pages of handwriting comprised by four folded signatures. The unknown handwriting is accompanied

in those very same folded sheets by the handwriting of known Mormon scribes who set down their dicatation from Joseph

Smith many years after the 1816 death of Solomon Spalding. All of these several facts appear to preclude any possibility

that Solomon Spalding could have written the portion of the Book of Mormon manuscript attributed to him by the three

California researchers.

As the Tanners point out, the simplest answer to various questions in this matter is that the 12 pages, along with the

rest of the preserved pages of Mormon manuscript, were all written at approximately the same time, in the same general

place, and under Smith's close supervision.

In a subsequent discussion the Tanners point out that the content of the 12 pages is steeped in religious language and

covers religious concerns which have never been associated with Spalding's personal or professional views. Many early

witnesses stated that the Spalding work they recalled was fairly devoid of religious material of this sort. Here the

Tanners stand on less solid ground in forming their assumptions and conclusions. The Oberlin Spalding manuscript does

include a considerable amount of religious language and it does address some religious concerns, albeit not in phraseology

or a viewpoint seen in the 12 Mormon pages. It remains uncertain whether the witnesses who reported reading (or hearing

read) certain portions of Spalding's writings were fully exposed to all that he wrote or whether they retained

full recollections of even those portions of his fiction which they encountered many years before providing their sundry

statements. The frequently voiced Mormon notion, that D. P. Hurlbut influenced the wording of several of these witnesses'

statements, might also be brought into consideration at this point. So, while the Tanners are justified in raising this

particular point for investigation, the amount and nature of "religious matter" in Solomon Spalding's lost fictional

writings remains undetermined.

My own textual findings, developed over the course of many

years of investigation, lead me to the conclusion that the LDS edition's I Nephi 4:20 to I Nephi 12:08 is a mixed lot of

material, possibly drawn from different sources and very likely redacted by an editor of the late 1820s, to conform with

the Christianity (and supposed proto-Christianity) portrayed throughout most of the Book of Mormon story. The parts of the

I Nephi textual block showing the greatest

affinity with the phraseology and thematic

elements found in Spalding's Oberlin manuscript are to be found in the pericope relating the murder of Laban and in the

following episode, relating Lehi's dream.

The remainder of the text (with the possible exception of the last few verses on page 12) is very much unlike

what little is known of Spalding's personal concerns and writing style. Had the I Nephi block of handwriting attributed to

Spalding by the California researchers coincided more perfectly with these

"Spaldingish" sections of the Mormon narrative

on those 12 pages, I might have been tempted to consider the case for some inexplicable retention of Spalding's original

sheets within the body of the Mormon manuscript. As it now stands however, the probable evidence for a late redactional

insertions in the last few of the 12 pages, merely reinforces my original view, that the scribe of this work could NOT

have been Solomon Spalding. The baptismal concerns of 11:27 and other specialized Christian theological elements point

more probably in the direction of a post-1823 reformer among the American "Reformed" Baptists -- in short, to a person

more like Sidney Rigdon, Orson Hyde, or Parley P. Pratt -- than to an

unorthodox Deist and would-be

satirist of Christian religious practices

(like the ex-Reverend Solomon Spalding).

The Tanners' major contribution to studies of the Spalding-Rigdon Authorship Theory is that they have effectively demonstrated

Spalding did NOT personally write certain pages extant in the LDS Archives. This was a commendable effort on their part

and it deserves acknowledgment. However, it does not necessarily follow that Spalding's writings had no connection

whatever with the composition of the Mormon book. While the scribe who wrote the "12 pages" remains unidentified, the

penmanship set down there may just as well have belonged to Sidney Rigdon or Parley P. Pratt as to any other early Mormon.

If either of these two men can be identified as the unknown writer, the traditional Spalding claims would be strengthened

just as much as if the handwriting belonged to Solomon Spalding himself. So, the Tanners' rejection of the "Spalding

theory" need not be considered the final word on Mormon origins, merely because they correctly debunked the "12 pages"

claims of 1977.

05. Where the Tanners Have Gone Astray

From page 7 of their "Part 1" onward, the Tanners present their views on the "Origin of Spalding Theory." Skipping

deftly past James Gordon Bennett's 1831 report

of a Rigdon authorship (which was evidently based upon interviews in the Palmyra area with people familiar with the Smith

family for a number of years) the critical couple instead pick up Alexander Campbell's published notions from that same

year. Their quote from Campbell is:

When the Book of Mormon first appeared in 1830 it was believed to be the work of Joseph Smith. In 1831 Alexander

Campbell wrote: "And yet for uniformity of style, there never was a book more evidently written by one set of

fingers... this book was written by one man, And as Joseph Smith is a very ignorant man and is called the author on the

title page, I cannot doubt for a single moment but that he is the sole author and proprietor of it."

(Millennial Harbinger, Feb. 1831,

p. 93)

What the anti-Mormon writers do not tell their readers is that Campbell was not a subscriber to the historical-critical

method for analyzing scriptural works and that he would have not recognized composite "holy writ" had it been laid down

in front of him accompanied by explanatory notes and diagrams. Also, Campbell at that early date, was not about to write

off the defection of Sidney Rigdon's Mentor and Kirtland followers from his own ranks into those of the Mormons as an

irretrievable loss. His father, Thomas Campbell, was trying to rescue the lost Rigdonite sheep in Ohio, even as

Alexander was first perusing the Book of Mormon. The Campbells had no desire to totally lose their influence over Elder

Rigdon, especially so knowing that he could air a substantial quantity of their own dirty laundry, should he take a mind

to do that. Alexander Campbell was no doubt treading lightly with Rigdon at this point and was implicitly offering his

old lieutenant absolution from blame in the founding of Mormonism, should Sidney ever come to his senses and quit the

Mormonite "restoration of all things" business. Alexander continued this implicit policy, by allowing one of his admirers

to publish the 1832 "Delusions" pamphlet,

restating his Millennial Harbinger article's focus on Joseph Smith as the culprit writer.

However, a few years later, in the very same newspaper, Rev. Campbell would have something rather different to say about

the origin of the Book of Mormon:

Brethren Scott and Bentley are both mistaken as to the fact of baptism for the remission of sins not

having been found in the Book of Mormon... the inference of brother Scott touching the person upon

whom the theft was committed would be plausible, if it was a fact that baptism for remission of sins

is no part of the Book, but something superadded since from the practice in Ohio in the end of 1827

and beginning of 1828, a year or more after Rigdon made the aforesaid statement.

But the truth of this inference depends upon the fact whether baptism as aforesaid is found in the

Book of Mormon, or was, as he imagines, borrowed in 1830 from some of our brethren on the Reserve.

Baptism for remission is, however, taught in the Book of Mormon, and therefore, according to his

[Elder Scott's] own reasoning, the inference is wholly an imagination. It is found variously and

frequently stated in the Book of Mormon. On page 479 it is expressed in the following words: "Blessed

are they which shall believe in your words, and be baptized: for they shall be visited with fire and

the Holy Ghost, and shall receive a remission of their sins." Again, p. 581: "Baptism is unto repentance

for the fulfilling the commandments unto the remission of sins." Again, p. 582: "The first point of

repentance is baptism, and baptism cometh by faith unto the fulfilling of the commandment, and the

fulfilling of the commandment is unto the remission of sins." Indeed, as early as page 240 it is plainly

taught in the form of a precept: "Come and be baptized unto repentance, that you may be washed from your

sins." Certainly this is testimony enough, without further reading. The note on the text of brother Bentley's

letter shows how easily men may reason wrong from false facts, or from assumed premises. If the editor of

the Evangelist were not above the

imputation of ambition, jealousy, or vanity, the whole affair might be construed disadvantageously. But as

it is, it seems to show the necessity of a scrupulous examination of the premise before we presume on

such grave conclusions... that Sidney Rigdon had a hand in the manufacture of the religious part of the

Book of Mormon is clearly established from this fact, and from other expressions in that book, as certainly

"stolen" from our brethren as that he once was among them...

Millennial Harbinger, Jan. 1844

In other words, what Rev. Campbell was not ready to deal with in the winter of 1830-31, he finally

was ready to address1 in 1844, when he accused Rigdon of stealing the "expressions

in that book" from Disciples of Christ theological promulgations. The particular element Campbell chose to focus

upon was the doctrine of baptism for the remission of sins, which was largely a conversion innovation championed by

Sidney Rigdon's closest mentor among the "Reformed Baptists" (later Disciples of Christ), Elder Walter Scott. Scott had

introduced this element of the Campbellite "ancient gospel," as Rev. Alexander Campbell relates, "in Ohio in the end of

1827" and Alexander further asserts that Sidney Rigdon then picked up the doctrine and inserted it as "something

superadded" into a Book of Mormon manuscript Rigdon was

then compiling.

Of course, just because Alexander Campbell said something was so, that doesn't make it true. The famed LDS apologist

B. H. Roberts was later able to punch some seeming

holes in Campbell's 1844 assertions. But the fact stands that Rev. Campbell was in the best position to recognize his and

Scott's theological innovations, if they had been appropriated and placed within someone else's book. It would be

disingenuous to maintain that Campbell could not see his own theology (or Rigdon's perversion of it) staring at him from

practically every chapter in the Book of Mormon. At least

Daniel P. Kidder could see that as early as

1842. And Clark Braden and

William H. Whitsitt would later see the same thing. We should not

accept Campbell's 1831 statement too literally, without first looking carefully at what he had to say in

1835 and

1844.

The Brodie Factor

The Tanners go directly from citing Rev. Campbell to citing Mrs. Fawn M. Brodie, in much the same way that

Brodie herself moves from Campbell's 1831 statement on probable

Book of Mormon authorship directly into her own pet idea -- that Joseph Smith wrote the Mormon scriptures all by himself.

Here is what I said about Brodie in

another review:

Despite her vilification of Smith and her eventual break with the LDS Church,

the reader of her original edition and its 1977 enlargement can discover a strange

kind of hero-worship in Brodie's writing. She saw Smith as being fully capable of

writing the Book of Mormon, even during his semi-literate youthful years. Brodie

could not fathom how anyone other than Smith could have ever produced such a marvelous

work and wonder.

In laying all the literary credit at Smith's feet, Brodie threw out the window any

possibility for previous contributors to the Book of Mormon text, be they ancient

Nephites or broken down former clergymen of the past century. And, although she began

her work as an LDS member in good standing, with her book publication and excommunication

she quickly became the darling of the anti-Mormons. More than any other writer this

century, it has been Fawn M. Brodie who has quashed the Spalding Authorship Theory.

And here is what I said about the same writer in yet another examination of her work:

The Tanners' consideration of the Spalding claims and their subsequent reporting on the matter duplicates the

thinking and arguments of Fawn M. Brodie almost exactly. The Tanners label Brodie as having been an

"anti-Mormon writer," although she was a fully-fellowshipped member of the LDS Church at the time she wrote

and published her 1945 book. Brodie was an LDS rationalist and would-be reformer, rather than an avowed enemy

of the Mormons. Brodie's investigation of the Spalding claims was superficial and solidly within the tradition

established by previous Mormon writers like

George Reynolds and

B. H. Roberts. In their close following of Brodie's

reporting, the Tanners ultimately draw upon old Mormon polemics and sanitized histories for their "facts" and opinions.

Brodie's primary thesis (other than her almost worshipful opinions regarding Smith's presumed super-human abilities)

is that D. P. Hurlbut so influenced the writing of the statements he took in 1833 from former associates of Solomon

Spalding that they are practically worthless as reliable documents. Brodie's hasty conclusion in this matter was

gleefully welcomed by her former co-religionists and modern Mormon apologists never tire of telling their readers that

no honest person can possibly make good use anything which has passed through the hands of D. P. Hurlbut or E. D. Howe

in "faithful" historical reporting. While Hurlbut's promptings may have indeed colored wording in some or all of the

statements he gathered, it is illogical to suppose that while in Conneaut, Ohio in August and September of 1833 (weeks

before the anti-Mormon investigator reached Manchester, Palmyra, and Otsego Co. New York, or Monson, Massachusetts)

Mr. Hurlbut was already manufacturing witness statements out of whole cloth and having no evident concern for possible

facts -- that is, for the unique historical details Spalding's old associates and family might be able to share with

him (and his financial backers). Hurlbut needed those details in to plan and pursue the remainder of his quest, and

he no doubt encouraged their telling and recording. Hurlbut only heard of the alleged Spalding/Book of Mormon connection

after some people in and around Conneaut, Ohio were already talking about this oddity of textual similarity.

He did not (as some apologists would have investigators believe) dream up the textual resemblance allegations himself

and then induce people in the area to subscribe to them as deliberate falsifiers or largely ignorant puppets. The witness

testimony taken by D. P. Hurlbut, to a great extent, corroborates and supplements testimony offered by other Spalding

associates whom Hurlbut never encountered. It is totally unreasonable to suppose that his "coaching" of Ohio witnesses in

1833 somehow reached across time and space to greatly influence the wording of all this additional testimony from other

sources. An LDS apologist might argue (as some have) that Satan's vast powers of unholy persuasion allow for the virtual

cooperation of "enemies of the latter day work," even when the persons involved in the persecution of the Saints are not

fully aware of the pernicious influence. Happily, Fawn Brodie and the Tanners do not go so far in their arguments against

the Spalding claims to suggest the manifestation any such supernatural control.

Also to the Tanners' credit, they do not launch into an old-fashioned attempt to totally discredit and demonize the early

Ohio witnesses for the Spalding authorship claims (that sort of approach was more in keeping with the old methods of LDS

ultra-polemicists like Joseph F. Smith). The Tanners

appear to be more interested in Fawn Brodie's strange assertion, that Solomon Spalding never wrote more than one

fictional story in his life and that the single "lost" story in question was found in Honolulu

in 1884. In Brodie's view (and that of the Tanners)

the Oberlin Spalding manuscript has no similarity at all

to the Book of Mormon. Since the Oberlin document simply must be the only story Spalding ever wrote; the only one

ever read by and shown to the folks around Conneaut; and the only holograph MR. Hurlbut ever recovered; then it obviously

must follow that the writings of Solomon Spalding have no connection whatever with the Book of Mormon text. Or so

say Mrs. Brodie and her far-famed disciples, Jerald and Sandra.

Before proceding with comments on this particular point, I must take the time to reproduce a seldom-quoted (but potentially

very important) piece of correspondence from Conneaut, Ohio, composed at the very end of 1833. By that time D. P. Hurlbut

had returned from his investigative efforts in the

East and was calling upon the Conneaut store-keeper Aaron Wright, whose statement he had previously solicited, near the

end of August of that same year. This seldom-quoted

letter reads thusly:

[obverse]

Dear [Sir]

Whereas I have been informed that you have been appointed with others to investigate

the subject of mormonism and a resolution has been past to ascertain the real orrigin of the [said] Book this

is therefore to inform you that I have made a statement to Dr. Hurlbut relative to writings of S Spalding Esqr

[said] Hurlbut is now at my store I have examined the writings which he has obtained from [sd] Spaldings

widowe I recognise them to be the writings handwriting of [said] Spalding but not the manuscript I

had refferance to in my statement before alluded to as he informed me he wrote in the first place

he wrote for his own amusement and then altered his plan and commenced writing a

history of the first settlement of America the particulars you will find in my testimony dated Sept 1833

August 1833 -- for years before he left this place I was quite intimate with [sd S] Spalding

we had many private interviews the history he was writing was the topic of his conversation relating his

progress and contemplating the avails of the same ---

I also contemplated reading his history but never saw it in print untill I saw the Book of Mormon where I find much

of the history and the names verbatim the Book of mormon does not contain all the writings [said] Spaldings

I expect to see them if

[reverse]

Smith is permitted to go on and as he says get his other plates the first time that Mr Hyde a mormon

Preacher from Kirtland preached in the [centre] school house in this place the Hon Nehmiah King attended as soon

as Hyde had got through King left the house and said that Hide had preached from the writings of S Spalding

In conclusion I will observe that the names and most of the historical part of the Book of Mormon is as familiar

to me as most modern history [if] is not Spaldings writings copied it is the same as he wrote and if Smith was

inspired I think it was by the same Spirit that Spalding possessed which he confessed to be the love of money,

Coneaut Dec 31 1833 Ashtabula Co [O.]

Due the bearer on demand one hundred

and fifty dollars in good merchantable

[lotte upon] the first day of Oct next

witness[ed]

Ro[gar] Mill[a]r

Here is an important, primary source document, preserved by the Wright-Lake family of Conneaut, and eventually donated to

the New York Public Library in 1914.

Did D. P. Hurlbut tamper with this document's wording, as well as with each and every statement he collected from the

eight "Conneaut witnesses?" I suppose anything is possible -- the

handwriting on the antique paper may even be that of

Mr. Hurlbut himself -- but in my view this old letter serves to strengthen the likely reliabity of the Conneaut witnesses.

Essentially this document affirms that Elder

Orson Hyde came to Conneaut (on his 1832

missionary trek eastward from Kirtland with

Samuel H. Smith) and preached from the Book of Mormon.

One of Solomon Spalding's old associates, "Judge" Nehemiah King, heard Hyde's sermon and recognized his quotes from the

Book of Mormon as resembling what the Judge remembered of Spalding's fictional writings. From Judge King the message soon

spread throughout the Conneaut area that Mormons were preaching from an old Ohio pioneer's unpublished fiction.

Elder Hyde returned to the Conneaut region shortly after Eber D. Howe's

1834 anti-Mormon book was published, but the Mormon elder

was markedly unsuccessful in gathering any useful evidence against the Conneaut witnesses and their published testimony.

We can be very sure that Hyde would have presented anything he found in their disfavor when he related the story of his

fact-finding and damage control work to Elder George J. Adams on

June 7, 1841. And, before readers are too quick to

believe all that Hyde has to say, they might well recall that it was he who first brought charges against D. P. Hurlbut

for Hurlbut's alleged improper behavior with a certain Mormon girl in Erie County, Pennsylvania in 1833; and it was this

same Orson Hyde who was almost immediately thereafter promoted from walking the cold, muddy roads of the mission field to

a position of repose and comfort as Joseph Smith's clerk's in Mormon President's cozy Kirtland office. If any of what

Hurlbut was saying regarding Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon and Mormon origins in those days of yore was true, then Orson

Hyde stood to gain little by doing anything other than suppressing that message. And, it seems Elder Hyde did all that he

could to defame and disarm his former missionary partner (Hurlbut proslyted with Hyde in the

Conneaut area early in 1833).

At this point, the careful investigator might ask why it was that Elder Orson Hyde and his Mormon associates did not

bother themselves in taking down statements refuting the Spalding claims, and especially so when

Mormon converts who had known Spalding personally

were living practically next door to the eight Conneaut witnesses publicized in Howe's book. Although the Conneaut

witnesses have been made to bear the derision of writers like Brodie for any decades, their statements have yet to be

examined carefully and systematically to determine

what portions of them are undeniably true, what

portions are suspect, and what, if any, lies might be found in them. In following so easily after Brodie, the Tanners

have denied themselves the adventure of that inquiry. Sandra and her associates would be well advised to go back and

take a second good look at the whole matter.

06. Getting Back on Track

The final pages of the Tanners' Part 1 are taken up with a discussion called "Suppression of the Manuscript." Although

they give the initial appearance of having delved into the Spalding authorship theory, just a quick glance at their

citations reveals to the critical observer the embarrassing fact, that Jerald and Sandra rushed through their homework

rather too quickly the night they cobbled together their excuse for an exposition on the old authorship claims. The

couple's reliance upon Brodie, Kirkham, Fairchild, etc., for factual information is wonderfully naive, if not truly

malicious. Although the Tanners accuse Eber D. Howe of "suppressing" the document now called the Oberlin Spalding

manuscript, they also admit with straight faces that Mr. Howe provided his readers with a fair

summary of this unfinished "Roman Story" in his

1834 book. If Hurlbut and Howe wished to "suppress" the "Roman Story," its summary and the various facts related to its

1833 recovery would never have appeared in Mr. Howe's Mormonism Unvailed. If Howe and Hurlbut were guilty of

suppressing a particular old Solomon Spalding holograph, it obviously was not the Oberlin document. While Howe

later told of the unfriendly reception he gave to

Elder W. W. Phelps, when the Mormon came to visit his office, no person has ever claimed that Mr. Howe ever refused to

allow applicants a perusal of the Spalding manuscript in his keeping during 1834-35. In the latter year E. D. Howe

retired from the newspaper business -- although he never returned the "Roman Story" to its right owner (Spalding's widow),

the very fact that it survived seemingly untouched until 1884, indicates that he did not damage or destroy the document.

As late as 1881 Mr. Howe appeared willing to

discuss the contents of the "Roman Story," and to admit freely that it was basically unlike the reported "Manuscript

Found" -- an entirely different Spalding story, which he "concluded... was very much like the Mormon Bible."

Spalding's widow gave nothing to her uninvited visitor, D. P. Hurlbut, except a note of instruction addressed to her

cousin's husband, Jerome Clark, allowing Hurlbut to rummage through Solomon Spalding's old papers, and take away to

Ohio whatever holograph pages might appear to match the story in the Mormons' holy book. It would be idiotic to suggest

that Mr. Hurlbut, after traveling for so long and so far on his manuscript quest, never bothered to look at the pages

entrusted to him (c. Nov. 25, 1833)

at the Clark residence in Otsego county, New York. It is equally absurd to suggest that Hurlbut

would have bothered to acquire any of Spalding's writings which might not, in one way or another, suit his purposes. He

knew very well what he was carrying back to his anti-Mormon associates in Ohio. Hurlbut had promised Spalding's widow

he would publish whatever portion of her husband's writings that might match the Book of Mormon: E. D. Howe never made

such a promise. And it was Hurlbut who reportedly first wrote back to Spalding's widow, informing her that he had indeed

found the manuscript he was seeking. Hurlbut said much the same in his

press release, published in the Palmyra

Wayne Sentinel on Dec. 20, 1833, revealing that: "...he has suceeded in accomplishing the object of his mission..."

in the East. The Tanners, whose various publications contain frequent quotations from old issues of the Sentinel,

evidently did not find this particular article a useful source in their exposition of the Spalding authorship claims.

At this late date it is impossible to determine the full extent of any documents, notes or personal conclusions which

D. P. Hurlbut turned over to E. D. Howe at the end of January, 1834. Howe's only known description of that secretive

transaction is contained in two sentences that he penned on

Feb. 4, 1834: "I have taken all the letters

and documents from Mr. Hurlbut, with a view to their publication. An astonishing mass has been collected by him and

others, who have determined to lay open the [Mormon] imposition to the world." Whatever it was that D. P. Hurlbut gave

him in January, 1834, Eber D. Howe was not operating under any direct commitment to publish Spalding's "Roman Story;" nor

was he in any way directly obligated to Spalding's widow, in the matter of seeing that any particular documents were

returned to her. All of Howe's known dealings were with Hurlbut, or were with nearby witnesses who themselves had dealt

with Hurlbut. It is admittedly a peculiar development, that Mr. Howe did not contact and interrogate Spalding's

widow for more useful information. But perhaps, by mid-1834, E. D. Howe had his own, unvoiced reasons for not ferreting

out any further details on Spalding and his fictional writings.

Bait and Switch Tactics?

It was not for D. P. Hurlbut's delivery of the "Roman Story" into his hands that Howe paid Hurlbut off with $50 in cash

and the promise of numerous copies of Mormonism Unvailed, once the book had been printed. Howe paid the erstwhile

anti-Mormon researcher for the anti-Smith statements collected in New York along with whatever other "letters and

documents" the publisher hoped would be useful in exposing the saintly "imposition to the world." It is conceivable that

Hurlbut tricked Howe into buying the "Roman story," under the false assertion that it was a far better match with the

Book of Mormon text than it really was -- but even this possibility is difficult to account for, in light of the

information provided in the Dec. 31, 1833 Aaron Wright document, already mentioned. Hurlbut went to a considerable effort

to obtain documention of Spalding's handwriting from people in Conneaut who had known the man personally -- who may have

retained old documents in Spalding's handwriting

-- but he did so displaying only the "Roman Story," and not until after he first returned to Kirtland and there

openly exhibited Spalding pages which seemingly confirmed the words of his press release: that he had "succeeded in

accomplishing the object of his mission." Hurlbut's activities during this period were confusingly mysterious, to say

the least.

Immediately after his return from the East, in late December 1833, Hurlbut went about Geauga county exhibiting a certain

Spalding work which, according to numerous witnesses, did resemble the text of the Book of Mormon. This is

supposed to have been the elusive "second" Spalding story -- the very supposition which is so much discounted both by

Mrs. Brodie and her disciples, the Tanners. This "second" Spalding holograph, which reportedly did resemble the

Book of Mormon text, was seen and its contents testified to by a number of residents in and about the town of Kirtland,

most notably by Hurlbut's own lawyer,

James Briggs, Esq., as well as by the Kirtland Justice of

the Peace, John C. Dowen. The Tanners must be

well aware of Briggs' testimony, for they printed a small part of it in their 1977 book, but stepping into the shoes of

dozens of Mormon apologists who came before them, they blithely dismiss such eye-witness evidence as being either

deliberate falsehood or the product mistaken memories. If all the similar testimony accumulated in support of the

Spalding authorship claims over the years is conscious falsification, then there must exist a vast diabolical conspiracy

of Gentiles and ex-Mormon apostates, working together in an evil secret combination to discredit invalidate the Book of

Mormon. This Satanic conspiracy explanation will be dismissed out of hand by rational investigators, leaving only two

reasonable options. If much (or all) of the Spalding claims testimony has been submitted by witnesses acting in good

faith, then its is either true, or must be credited to the "false memories" side of the controversy.

If the latter option be correct (as Brodie and the Tanners argue) then here is a bogus belief, steeped in manifest and

misbegotten mistakes spanning more than a dozen decades and encompassing perhaps as many as three dozen confused and

easily manipulated witnesses. Surely such a social phenomenon must be a prime candidate for page one in the collected

"believe it or not" accounts compiled by Mr. Ripley!

Eber D. Howe must have known, from at least mid-January 1834 onward, something about the "Roman story" Hurlbut had

brought back from Hartwick, New York. Howe must have also thought he might get from Hurlbut another Spalding story -- one

closely matching the account given in the Book of Mormon; but he didn't. Instead, Hurlbut handed over the "Roman story,"

along with various statements he had recently collected, and then disappeared from the scene. That is, Hurlbut handed

over at least the Roman story and a stack of anti-Mormon affidavits. Howe had no use for the "Roman story" and he

was probably never informed of Hurlbut's promise to return it to Spalding's widow. It was subsequently discarded,

forgotten, and unknowingly passed on to Lewis L. Rice when he purchased the Painesville Telegraph office and its

contents some years later. This is not a matter of "suppression," as the Tanners would have their readers believe. If

anything was "suppressed" it was the second Spalding manuscript -- the one exhibited by Hurlbut, but which Brodie

and the Tanners do not believe ever existed. There are numerous individual statements from persons unconnected in time

and space who testify that Solomon Spalding wrote many stories. His own adopted daughter recalled one he had written

especially for her. But, "no" say the Tanners, Spalding wrote only "one" story in his entire life and that manuscript is

on file today at Oberlin College. No doubt Spalding's little girl was also a victim of "mistaken memories," in thinking

that her foster father had ever written any thing other than an unfinished account about shipwrecked Romans.

Oddly enough, both Brodie and the Tanners are perfectly ready to trust Hurlbut when he says he recovered only a

single Spalding holograph from Jerome Clark's Hartwick garret, but they mistrust the same Hurlbut totally when he was

gathering witness statements in Ohio and Pennsylvania in support of the Spalding authorship claims. In the former

situation Hurlbut may have well been left alone with the famous old trunk by Mr. Clark. The seemingly disinterested

Clark family2 had no reason to watch over Hurlbut as he rummaged through Spalding's trunk.

While Mr. Clark was out milking the cows, perhaps Hurlbut was spending his time carefully reading each and every old sheet

of paper in the moth-eaten trunk. Who can today say exactly what he found tucked away among Spalding's old notes and

sermons? So far as history records, Hurlbut gave Mr. Clark no receipt -- no itemized list -- for whatever it was that

he stashed away inside his greatcoat or traveler's portmanteau on that cold November day. He may well have left Hartwick

with a dozen pounds of old manuscripts.

While searching about in the Conneaut region, Hurlbut was in

the collective company of many of Spalding's old neighbors and relatives. Had he then been fabricating a single statement

of any single witness, he was obviously also fabricating the whole lot of them -- and that too, with the witnesses'

consent or total disinterest. The Spalding authorship claims were known and discussed among several of the Conneaut

residents months before (and for years after) D. P. Hurlbut's coming upon the scene. Those very claims seem to have

influenced the defections of Conneaut area Mormon converts like Andrews Tyler. They may have had something to do with the

fact that 1833 was a very good year for missionary work in the Conneaut region, while 1834 was an abysmal one. And they

may have had something to do with the fact that the only two Mormon congregations in

close proximity to Conneaut were removed totally from the

scene, by the Mormon leadership, before the year 1836.

Given the fact that the Spalding claims were in circulation prior to Hurlbut's happening upon those wonders, it is

unlikely that he fabricated (or even greatly influenced) the wording of the statements he took from the eight Conneaut

witnesses. There is no particular reason for Brodie and the Tanners to trust Hurlbut any more when he was alone in

Hartwick than when he was in the company of the several Conneaut witnesses. As I've already stated, probably no person

but Hurlbut himself knew what he brought back to Ohio from Otsego County, New York. He took at least one more Spalding

document than the Oberlin manuscript proper (an

undated Spalding statement in the form of a draft letter); who

is to say that Hurlbut did not take much more? And, if Mrs. Mary W. Irvine's

1881 report (saying that Rigdon possessed a

Spalding-like manuscript in Pittsburgh, as early as 1823) attributed to Rigdon's fellow Baptist Minister John Winter,

can be credited, perhaps historians should look first to Rev. Rigdon for a

retained copy 3 of the lost second manuscript.

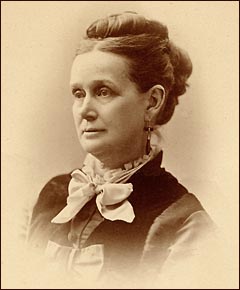

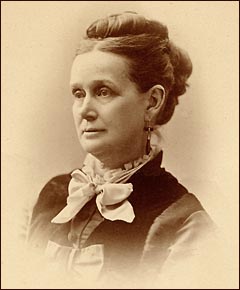

Mrs. Mary Winter Irvine (D. Broadhurst Coll.)

07. A Matter of Family Resemblance?

Following always directly in Brodie's footsteps, the Tanners believe that all of the witnesses who recalled that Spalding's

writings resembled the Book of Mormon were victims of "memory substitution" -- because the Book of Mormon bears "no

resemblance to the cheap cliches" found in the Oberlin manuscript and because "it is almost impossible to believe that

Hurlbut had more than one manuscript." This is woolly-headed reasoning at its worst and Sandra Tanner really should try

again to come up with some better explanation of why numerous witnesses in both the Conneaut, Ohio region and the Amity,

Pennsylvania area long retained their mutually corroborative recollections concerning Spalding's fictional stories.

Certainly no allegations of "memory substitution" can be attached to Josiah Spalding's excellent recollections of his

brother's "Roman story," as he wrote them down in his

Jan. 6, 1855 letter to

George Chapman. If brother Josiah Spalding could

well remember numerous petty details in one Solomon Spalding composition 40 years after the fact, there seems no

logical reason that brother John Spalding should be charged with near total forgetfulness (or "memory substitution")

20 years earlier, in recalling the details of

another Spalding literary creation (see also the summary of brother John's recollections published

in 1851, for an example of what what Brodie and the

Tanners would perhaps lable as tenaciously persistent "memory substitutions").

The dynamic duo of Deseret have written a good deal about Joseph Smith, Jr.'s wonderful writing abilities, but they

really have no idea what he was capable of composing way back in 1827. He seems to have had trouble enough just getting

the Nephite narrative dictated to his scribes. It would have been a marvelous work and wonder indeed if he had possessed

the skills, patience, industry and willingness to produce "the record" out of thin air at his own writing bench, even

with Palmyra news clippings and visits to the local library thrown in for good measure. Did Joseph pick up and insert into

his Book of Mormon Livy's "Helorum" following a random glance into the pages of a well stocked frontier library's

classical section? Or did Joseph select and make use of Shakespeare's

"watery grave" due to his scholarly delight in

studying the Bard of Avon after a hard day's plowing (and a long night's treasure hunting)? Joseph the scribner must have

possessed quite a literary mind to reproduce

Ossianic warriors "leaning" on their weapons. And no

doubt his his deep love of Virgil introduced him to the Latin poet's

Nissus story and gave the young posey affectionado the

idea for Teancum's sneaking into the camps of sleeping enemies? I seriously doubt the value of any such a "love of

literature" explanation on Joseph's part. If we are to place Smith into the Manchester/Harmony creative historical

writing projects of 1828 it must be as neophyte final redactor -- perhaps even as selector and abridger of "the record"

-- but not as its creator. Where? I might ask the Tanners, is the evidence for Joseph having been such a scholar

and writer? Where are the statements of witnesses who stumbled upon him as he sat bent over his ink-stained writing desk?

Where are the abandoned first drafts and fragments of writings, such all authors of fiction churn out as they go about

their tedious labors? Where are his notes on counter-Universalist theological polemics and Campbellite baptismal

regeneration rhetoric? The old Mormon argument of the ignorant farm-boy being unable to write the book is far more

convincing than anything Brodie or the Tanners have ever concocted in their respective Smith-as-author scenarios. And all

of the psychological-literary forensics of

I. Woodbridge Riley and

Dan Vogel to the contrary nothwithstanding, the

young Joseph Smith, Jr. is a truly awful candidate for the "one true author" of the early LDS scriptures. And that

fact may have precisely why Sidney Rigdon reportedly chose the glass-looker as his restoration gospel front man.

If Smith's Kirtland era vocabulary appears to echo that of the Book of Mormon, perhaps it is just that -- an echo left

over from his constant exposure to, and frequent use of, what may well have been the first book he ever read from cover

to cover. The Tanners are able to picture the literate Rev. Rigdon acting as the Smith's lowly scribe during their joint

project of re-writing the English Bible. Why can't they picture that educated Campbellite preacher functioning as Joseph's

grammar and scriptural tutor as well? Either Rigdon was baptized a Mormon, as a true believer, and then went right

to work manufacturing ersatz scriptures with Smith (as his suddenly savvy collusionist), or else Sidney's conversion to

Mormonism was just as contrived as had been his

faked conversion to the Peter's Creek Baptist Church

many years before. So which is it, Sandra? Was the pious Rev. Rigdon so enchanted by Smith that he quickly abandoned his

Christian morals, sat down with the "First Elder," and began to manufacture whole new chapters for the "Inspired Version"

out of thin air? Or, had Rigdon and Smith been playing the same secretive scripture writing confidence game together, back

as early as 1827? In his 1844 Spring

Conference speech, delivered before a saintly audience at

Nauvoo, Rigdon inexplicibly reveals that he was present in New York when the Mormon Church was first beginning -- that he

and other early Mormon leaders met and acted in secret, in the days when they all could fit inside of a single log cabin.

Was this his inadvertant admission of pre-1831 visits among the earliest Mormons, or was that just another in the

seemingly endless series of holy tale-telling Sidney Rigdon passed on to deluded auditors?

Lucy Smith (in Kirtland) and the post-Smith Mormon leadership (at Nauvoo) both accused Rigdon of lying in the name of

the Lord, in different situations. Jedediah M. Grant and

Orson Hyde would have us believe that Sidney Rigdon was an

invenerate liar, wickedly engaged in all manner of secret ecclesiastical scheming. And, even if the Tanners give Sidney

the benefit of the doubt, in some modicum of religious veracity during his years in the LDS Church, after July of 1844 he

was either a holy liar or a true prophet of God. If we choose to believe the former (as I think the Tanners must), then

why must we exempt this saintly scamp from holy tale-telling back in 1830? The Tanners could have done much better -- they

might have at least supplemented their readings in "Spalding theory" history with an occasional consultation of

Theodore Schroeder. Or, failing their perusal of that

source, Charles A. Shook,

Clark Braden or

George Arbaugh might have enlightened them just a little on

historical matters. And, should the fearless fighters of Mormonism disdain even these informative tomes, there are

several hefty stacks on unpublished primary documents supportive of the Spalding claims which I myself can send Sandra's

way at any time. I doubt the offer of free research assistance will be accepted, however. In 1998 I extended the couple

the free gift of $1000 -- just to take a look at such materials. They of course declined the offer and the investigation.

Along with Mrs. Brodie, the Salt Lake pair fail to find any humor in the Book of Mormon. This is a strange rebuttal against

the Spalding claims. Like Dialogue writer Mark D. Thomas, I see see substantial portions of the work as being a

parody. This is exactly the word Thomas uses in his 1996 "A Mosaic for a Religious Counterculture: The Bible in the Book

of Mormon." I personally find the scene of Ammon slicing off countless arms of oncoming clubsmen to be fine dry humor --

it might have been made even more comical through a sardonic "dramatic reading" before a live audience. The story

describing Shiz's disconnected head grasping for breath is just as amusing as any of Spalding's mock epic scenes in the

"Roman Story" (not to mention his tales of fat ladies almost drowning their lovers in the muck). The ex-clergyman's

Oberlin manuscript is not just the "Gothic romance" and imitation of "eigteenth-century British sentimental novelists"

Brodie's unfocused eyes saw -- it is a

complex pastiche, made up of bits and pieces of

Pope's Homer, Dryden's Virgil, Livy's Roman History, James McPherson's

Ossianic tales, the

KJV Bible,

and Mercy O. Warren's writings, with perhaps a few extracts from

Tom Paine, the Federalist Papers, the Compte de Volney, and James Bruce's travels thrown in for added spice. If one

cannot find "and it came to pass" endlessly repeated in Spalding, there are certainly enough other repetitious "cheap

cliches" drawn from classical, contemporary, and even biblical sources. The Oberlin manuscript is "Pope's Rape of the

Lock coupled Robert Southey's Madoc, minus the

poetry of both. Has anyone ever noticed that the Book of Mormon is Virgil's Aeneid coupled with Second

Maccabees, (minus the true antiquity of both)? There is much to be learned here, but the Tanners appear to have been

content to sit in a corner with their backs to a great deal of useful literary and historical reading material.

As I've said, the one interesting source they do manage to quote is James A. Briggs, the lawyer who represented D. P.

Hurlbut, in Ohio during the winter of 1833-34. Mr. Briggs' various statements concerning this obscure episode shed a good

deal of light on Kirtland area goings-on prior to the publication of Howe's book and it's a pity that the anti-Mormon

married team did not look just a tad deeper into the story at that point. Had they taken the trouble to set aside their

dog-eared copy of Brodie, and sunk their teeth into some real Spalding claims "meat," perhaps their readers might have

been blessed with something more useful from Modern Microfilm typewriter. The evident results of the Tanner's merely

scratching the surface of this important issue in Mormon history are altogether lamentable. About all they manage to do

is to reinforce, in my opinion, the statement I heard in Lamoni years ago: perhaps Jerald and Sandra "ought to be put on

the payroll" of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

08. Final Thoughts

In some of their other writings the Tanners have done a fairly decent job of finding evidence for Nephite borrowings out

of every source from Shakespeare to the Westminster Confession, and from Josiah Priest to the Introduction of the KJV

Bible. The one source they have neglected to look into is, of course, Solomon Spalding. Though Utah Lighthouse Ministries

publishes and distributes a barely legible reproduction of Spalding's Oberlin manuscript in the five-part volume on the

Spalding theory, the Tanners appear to have never even browsed its contents. A cursory examination of that work turns up

piles of

parallel passages like these:

Spalding:

those who shall die... in the cause of their country and their God

B. of M.:

they have died in the cause of their country and of their God

Spalding:

Determined to conquer or die,

B. of M.:

they were determined to conquer in this place or die

Spalding:

It is impossible to describe the horror of the bloody scene . . .

the blood and carnage

B. of M.:

It is impossible... to describe... the horrible scene of

the blood and carnage

There are literally hundreds, perhaps thousands, of shorter

textual overlaps

between the two works. The thematic parallels, as Bown,

Bales, and

Holley have demonstrated, are equally extensive. Were the

Oberlin manuscript comprised of as many pages as is the Book of Mormon, the textual evidence alone would probably be

overwhelming. But it is a short work, quickly scribbled and left unfinished. Its parallels with the Book of Mormon are

significant but not conclusive. And, as I've said more than

once, our discovery of textual

and thematic parallels alone should not induce us trumpet to the world that Spalding wrote the Book of Mormon. Similarly,

the readily available sources of historical evidence in this relation are so scanty that we cannot yet rely upon them

as supplying difinitive proof that Spalding's name should be added to the Nephite frontispiece either. As for the more

obscure, less easily obtainable sources, their combined content does tip the balance indicator well over into the

traditional Spalding claims. The Tanners are not going to find these particular historical sources listed in their

copies of Reynolds, Roberts, Kirkham, and Brodie, however -- and for quite obvious reasons. Like beauty, proof of the

Spalding-Rigdon authorship theory lies in the subjective gaze of the attracted beholder.

Since the Tanners do not appear to have the slightest interest in looking over important, primary sources supporting

(even demonstrating, in some cases) the validity of a number of the Spalding claims, perhaps the best route for future

Tannerites to follow is the path marked out by the Book of Mormon's own internal literary hints and oddities. As

mentioned already, many of those hints lead in the direction of Alexander Campbell's theological doorway. Jerald and

Sandra have already dipped a toe or two, to test those historical and literary waters, but they have not come up with

any convincing explanations on how baptism for the remission of sins fits both into late 1820s Campbellism and into a

a set of golden plates, allegedly dug up in western New York in 1827. Neither have they followed their own Josiah Priest

and Ethan Smith hobbies back to the View of the Hebrews

author's reported association with fellow Dartmouth

graduate Solomon Spalding. There is so much remaining to be studied and reasonably explained here that a student like

myself (or a more vocal "ex-Mormon," like Byron Marchant) has good

reason to wonder aloud why this particular sleeping dog of Mormon history has been let lie for so many years.

Despite news accounts of law suits going on between the Tanners and the LDS Church, it appears all too likely that there

is a certain segment of that church's "middle management" which looks upon the couple with friendly eyes. The Tanners do

really do very little to rock the boat of Mormonism. Their supposedly hostile publications relieve a bit of pent up

churchly steam now and then, perhaps. Ideas and information concerning Mormonism which would have been especially

vexatious in Fawn Brodie's day and age can now be aired in public via publications written by the Tanners and others of

their class. From the Tanners' scribblings a few of those seemingly "radical" notions can slip over to the readers of

Dialogue and Sunstone. Cultural Mormons can nod their heads in agreement and volumes from Signature Books

can quote the Tanners second-hand. Life goes on and "all is well" (more or less) in Zion.

In the meanwhile Mormonism forges ahead, grows, adapts. Tannerism is not a reality in this large view of things; it is

but an illusory shadow. So long as the illusion persists -- that the Tannerites criticize "the Church" and that the

"faithful" apologists refute Tannerism -- the hidden agendas of the latter day leaders remain safely obscured and

unexamined. The true origins of Mormonism also remain safely "hid up" -- mysteries forever unknown and unknowable. Fawn

Brodie's fanciful image of LDS founder Joseph Smith, Jr. blends imperceptibly into the old "true blue" doctrines -- and in

this improbable synthesis the Saints find a comfortable continuum for their unexamined lives and scholars of the Mormon

past find a comfortable common ground, where believer and non-believer can meet and interact, without the old barrier of

"conspiracy theory" argumemts. But has the truth been told, or is it all a mirage, wrapped up in vision and lost in a

dream? In the final analysis, Mormonism and Tannerism prove to be but opposite ends of the same self-perpetuating paradeigm.

Sandra -- It's time to wake up and "smell the Postum."

notes:

1. Alexander Campbell was in no hurry to link his former close associate, Sidney Rigdon, to the authorship

of the Book of Mormon. When he finally got around to making that connection, it was not articulated in a direct attack

against his old lieutenant, but mamifested indirectly, through comments on the assertions of other writers. In early

1835 Campbell accepted the Spalding Authorship

claims and in 1839 he finally mentioned

Rigdon's name in this connection. However, it was not until 1844 that Campbell was ready to offer any personal

information on the subject

2. Spalding's adopted daughter, Matilda,

in 1880 remembered her mother instructing Jerome

Clark by letter to "open the trunk and deliver" one of her father's manuscripts to Hurlbut.

In 1885 Ellen E. Dickinson added an otherwise

unrecorded memory of Matilda's having learned that Jerome Clark in fact "opened the old trunk for the purpose."

Dickinson also says that Jerome Clark "retained part of the manuscript," but she provides no hard evidence for this

assertion. What likely happened is that Jerome Clark escorted Hurlbut to the desired trunk full of old papers, opened it,

and allowed Hurlbut to rummage through the contents as he liked. Whatever papers might have remained in the trunk

following this pillage would have perhaps been the "retained part of the manuscript" mentioned by Dickinson. There is

no record of the Clark family recalling and/or

reporting the details of this incident to anyone, following Hurlbut's departure from Hartwick.

3. Rev. Winter's reported disclosures regarding Sidney Rigdon at Pittsburgh, and his possession of the

writings of "A Presbyterian minister, Spaulding, whose health had failed," find probable confirmation in accounts left

by three other people who interected with Rigdon prior to his 1827 occupancy of the vacant pastoral office in the Baptist

congregation at Mentor, Ohio. After heleft Pittsburgh, and while he was living temporarily in Bainbridge township, Ohio,

Rigdon was visited there by his wife's neice, Amarilla Brooks (Dunlap), who

in 1879 said: "...During my visit Mr. Rigdon went

to his bedroom and took from a trunk which he kept locked a certain manuscript. He came out into the other room and

seated himself by the fireplace and commenced reading it. His wife at that moment came into the room and exclaimed,

'What! you're studying that thing again?' or something to that effect. She then added, 'I mean to burn that paper.'

He said, 'No, indeed, you will not. This will be a great thing some day!' Whenever he was reading this he was so

completely occupied that he seemed entirely unconscious of anything passing around him." Compare Amarilla's description

of Rigdon's literary preoccupation with this

paraphrased account, handed down from the

Rigdons' nursemaid, Dencey Adeline Thompson (Henry): "prior to... 1827... there was in the family... a 'writing medium,'

... and the Mormon Bible was written by two or three different persons by an automatic power which they believed was

inspiration direct from God... Rigdon, having learned, beyond a doubt, that the so-called dead could communicate

to the living, considered himself duly authorized by Jehovah to found a new church." This account is colored by the later

vocabulary of Spiritualism, but it appears to preserve evidence of a similar "literary preoccupation. FInally, consider

this paraphrased account, left behind by a teacher who taught school a stone's throw from the Rigdon's cabin in

Bainbridge; he says: "For a year or more

before the advent of Smith [in Ohio] they [neighbors in Ohio] saw that Rigdon was bent on devising some new dogma: in

short, to start a new church or sect that he could call his own or whose leadership he could share with only a few...

Rigdon did not preach that winter [1825-26], but was almost constantly engaged upon a manuscript that he was writing

or revising... towards the close of the term there was much more of it than there was [at] first..." Does it not seem

logical that Sidney Rigdon's stay at Bainbridge, Ohio should be given some closer historical scrutiny? See also Prof.

Craig Criddle's recent paper on this subject, "Sidney

Rigdon: Creating the Book of Mormon."

|

Associated Press wirephoto:

Associated Press wirephoto: