SOLOMON SPALDING

AT "LOCUST HILL"

________

Gerald Langford

The Richard Harding Davis Years

|

Document: 1813 Rachel Leet Wilson recollections (excerpt)

Source: Langford, Gerald The Richard Harding Davis Years, NY, 1961 Note: Langford's reference to Solomon Spalding having spent a winter (of 1815-16?) in the Hugh Wilson home, at "Locust Hill," one mile from Washington, Pennsylvania, was paraphrased from an entry written in Rebecca Harding Davis' "Manuscript Account" of her mother's and father's families. (The original was in the keeping of Mrs. Hope Davis Kehrig as late as the 1950s -- until its subsequent donation to the University of Virginia Library). |

J. M. Lasseter's 2001 book, Rebecca Harding Davis | transcriber's comments

|

G E R A L D L A N G F O R D The Richard Harding Davis Years A Biography of a Mother and Son Illustrated with Photographs HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON NEW YORK |

|

[iv] Copyright � 1961 by Gerald Langford All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. Published simultaneously in Canada by Holt, Rinehart and Winston of Canada, Limited. First Edition. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 61-5801 85141-0111 Printed in the united States of America ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For permission to quote from various sources, thanks are due to the following: Charles Scribner's Sons for a quotation from "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber" in The Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway (copyright 1953 by Charles Scribner's Sons); for quotations from Richard Harding Davis, [v] His Day, by Fairfax Downey (copyright 1933 by Charles Scribner's Sons; for quotations from The Adventures and Letters of Richard Harding Davis, edited by Charles Belmont Davis (copyright 1917 by Charles Scribner's Sons); for a quotation from Life's Adventures, by Elwood Worcester (copyright 1932 by Charles Scribner's Sons); and for quotations from the published works of Richard Harding Davis as specified in the notes; in particular, various titles included in The Novels and Stories of Richard Harding Davis (copyright 1916 by Charles Scribner's Sons). Houghton Mifflin Company for a quotation from The Martial Spirit, by Walter Millis (copyright 1931 by Houghton Mifflin Company). Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., for a quotation from Belgium, by Brand Whitlock (copyright 1919 by D. Appleton and Company). E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., for a quotation from The Confident Years, by Van Wyk Brooks (copyright 1952 by Van Wyl Brooks). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., for a quotation from The Mauve Decade, by Thomas Beer (copyright 1926 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.). G.P. Putnam's Sons for quotations from Front Line and Deadline, by Granville Fortescue (copyright 1937 by Granville Fortescue). Harper & Brothers for a quotation from The Development of the American Short Story, by Fred Lewis Pattee (copyright 1923 by Harper & Brothers). Sir William Rothenstein's Executors for a quotation from Men and Memories, by Sir William Rothenstein (copyright 1931 and 1932 by Coward McCann, Inc.). Mrs. Lloyd C. Griscom for quotations from Diplomatically Speaking, by Lloyd C. Griscom (copyright 1940 by Little, Brown and Company). The University of Pennsylvania for quotations from Rebecca Harding Davis, Pioneer Realist, by Helen Woodard Sheaffer (unpublished doctoral dissertation, 1947). The University of Kentucky for quotations from Richard Harding Davis, The Development of a Journalist, by Scott Compton Osborn (unpublished doctoral dissertation, 1953). Pages vi to xiv of this book were not transcribed. Excerpts from this copyrighted text limited to "fair use" length. |

|

Documentary

Excerpts from this copyrighted text limited to "fair use" length. |

J. M. Lasseter

Rebecca Harding Davis

|

Document: 1813 Rachel Leet Wilson recollections (excerpt)

Source: Lasseter, J. M. & Harris, S. M., Rebecca Harding Davis, Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2001 |

|

[137]

James Wilson, a farmer, and his wife, Margaret, came to this county from the North of Ireland about the year 1740, and went to a settlement in Eastern Pennsylvania which soon afterwards was destroyed by the Indians. It was afterwards known as The Burnt Cabins. The Wilsons escaped the massacre and crossed the Alleghanies. They chose a home on the hills where the town of Washington, Pennsylvania, now stands. They were the first white settlers in that place, their only friend for a long time being an old Indian chief named Tinguanquali. The two men were for years firm allies, and when they died, were buried side by side in the village graveyard, the white man under an ordinary lettered tomb-stone, the Indian beneath a huge blank rock. James Wilson brought enough capital to buy large tracts of land besides his homestead claims, and his son, Hugh Wilson, added to them so largely that when he made his yearly journey on horseback to Philadelphia over the mountains he used to boast that he slept every night on his own land. But he was so careless about looking after the taxes that the most of this land was sold to pay them. Hugh Wilson built the homestead, Locust Hill, in which his grandson James B. Wilson now lives. Hugh married Rachel Leet (See Leet family) and by her had four children. 1st: Rebecca, who married James Blaine... (remainder of page not transcribed - due to copyright restrictions) [138] (part of page not transcribed - due to copyright restrictions) ...When Hugh Wilson's daughters Rebecca and Margaret were married and settled, his wife gave birth to my mother, Rachel Leet, born August 1808, and two years later, to a son, Hugh W. Wilson. My grandmother died about 1816. My grandfather then married a Mrs. Fleming, his cousin who had by him one daughter Eliza, who married the Rev. Mr. Swaim. This second wife dying, my grandfather married an English woman, a Miss Spencer, who survived him but had no children. He gave my mother a different education from his elder daughters. His intimate friend was Bishop Alexander Campbell, the founder of the sect of "Disciples," a man who ranked among the half dozen great English scholars of his day. He received my mother into his family as a paying pupil, and educated her with his own daughters. She had an eager, hungry intellect... (remainder of page not transcribed - due to copyright restrictions) [139] (page not transcribed - due to copyright restrictions) [140] (page not transcribed - due to copyright restrictions) [141] My grandmother, Rachel Leet, the first Hugh Wilson's wife, was, according to tradition, an unusually able and very charming woman. She managed a large household in the old homestead, "Locust Hill," made up of her children, of bound women and men, black slaves and white Redemptionists, with singular skill and wisdom. She had both a shrewd business head and a devout, tender heart. While she lived the house was a refuge for poor folk, especially needy Baptist ministers, our grandfather being a zealous member of that sect. It was while one of those ministers, a Mr. Spaulding was spending the winter at Locust Hill, being too ill to preach, that he wrote a fictitious story which Joseph Smith published afterwards as the Book of Mormon. My mother who was a child of seven, then, remembered afterwards how she used to listen to the pale young man as he read aloud in the evenings what he had written during the day. My grandmother died when she was still a young, beautiful woman, leaving three daughters and a son. The account of them and of my grandfather's other wives is in the story of the Wilson family. I may add that our family of Leets were not related in any way to the Governor Leet in Connecticut who was famous for sheltering regicides. |

Rebecca Blaine Harding Davis (1831-1910) Granddaughter of Rachel Leet Wilson Rachel Leet Wilson was a Washington County girl who grew up on her father's country estate, located about a mile outside of the village of Washington. In her early childhood Rachel met the hopeful writer, Solomon Spalding, while he was lodging as a guest of her parents (Hugh and Rachel Wilson). According to one version of girl's account, she was then "a child of seven" who "remembered afterwards how she used to listen to the pale young man as he read aloud in the evenings what he had written during the day." There are two noticeable problems with this recollection: (1) Solomon Spalding (1761-1816) was no longer a "young man," during the final years of his life in Washington County; and, (2) Rachel Leet Wilson may have been somewhat younger than seven years of age, when Spalding spent his final winter (1815-1816) in Washington County. How "young" was Solomon Spalding? The first historical discrepancy is easily accounted for. The story is told second hand, by the lady's granddaughter, Rebecca Blaine Harding Davis, who may inserted the description "young" from her own faulty memory of the account. For example, if the word "young" is replaced with "slender," the Wilson girl's recollection can be matched with that provided by a contemporary friend of Mr. Spalding's, who said: "He was about six feet in height, with a large frame though much reduced in flesh, and weighing only about 150 pounds..." and, "He was afflicted with a serious rupture which prevented him from taking much exercise in the open air."

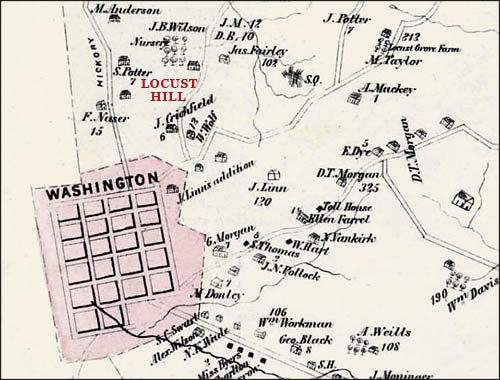

A sickly man, near the end of his life, who spent most of his time indoors, might be described as "pale," even if he had possessed a dark or ruddy complexion earlier in life. So, on the basis of a single problematic word, the Wilson girl's story should not be doubted. However, a more serious objection to her memories might be raised, on account of her own age, during the period Spalding is known to have resided in Washington County (Oct. 1814 - Oct. 1816). When was Rachel Leet Wilson born? Genealogical records of the Wilson family give 1808 as Rachel Leet Wilson's birth year, and that date is generally compatible with what little is known of her life and associations. For example, her granddaughter pinpoints the date: "Rachel Leet, born August 1808." If she was born late in 1808, the Wilson girl would have been about four years old, when the Spalding family first came to Pennsylvania (late in 1812) and resided temporarily in Pittsburgh. She might have really been nearly "a child of seven," during the first winter after the Spaldings moved across the county line into Washington's Amwell township (the township bordering her family's home township of South Strabane, on its southern border -- see map below). Rachel recalled that the literary-minded visitor "spent a whole winter in her home." If Mr. Spalding was her parents' house guest during the winter of 1814-15, the Wilson girl would have not yet been "a child of seven." A year later, during the winter of 1815-16, she would have been seven years old, and probably mature enough to form and preserve reasonably accurate memories. If the later date is accepted, then Rachel Leet Wilson's account might be relied upon in part, if not in full.

The Region around Washington Village, Washington County, Pennsylvania, (c. 1811) as it looked when Solomon Spalding was a guest in the Hugh Wilson home. The memory of a six-year-old cannot be relied upon in most cases. But, even if the Wilson girl related a fairly accurate account of Solomon Spalding's temporary residence in her parents' home, the likely date of that stay should be placed as late as practical within Spalding's known chronology. Perhaps the winter of 1815-16 can be guessed at, as the best possible fit with Spalding's biography and with little Rachel's age and youthful memories.

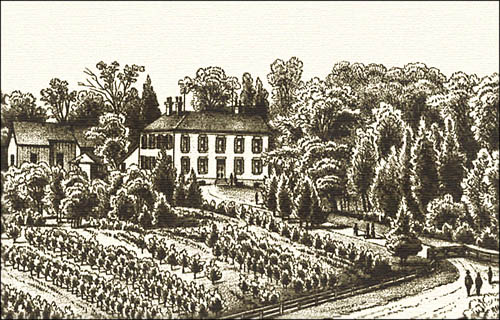

Hugh Wilson's "Locust Hill" estate, about a mile northeast of Washington Village, (c. 1876) during the period when the farm house was occupied by his son James B. Wilson.

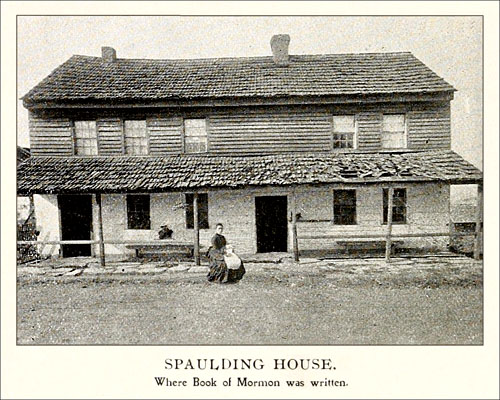

Hugh Wilson's "Locust Hill" estate (as it looked in 1876) Where was Solomon Spalding in 1815-16? The first published documentation of the Solomon Spalding family's migration to Washington County, Pennsylvania can be found in E. D. Howe's 1834 Mormonism Unvailed, where the editor quotes Spalding's old Ohio business partner, Henry Lake, as saying: "Spalding left here in 1812, and I furnished him the means to carry him to Pittsburgh, where he said he would get the book ["Manuscript Found"] printed." A few pages later he refers to Matilda Spalding Davison and her recollection of past events, thusly: "...the widow of Spalding... was found residing in Massachusetts. From her we learned that Spalding resided in Pittsburgh, about two years, when he removed to the township of Amity, Washington Co. Pa., where he lived about two years, and died in 1816." Assuming that these reports are accurate, the Solomon Spalding family's residence in Washington County must have spanned the year 1815, and included some portion of 1814 and 1816. Since he died at Amity on Oct. 20, 1816, after having lived there "about two years," his migration to that place evidently occurred during the second half of 1814. No additional light was shed upon Solomon Spalding's tenure in Washington County until 1839, when his widow supplied the following information during a personal interview: "...about the year 1812... we removed to Pittsburgh, Pa. Here Mr. Spaulding found an acquaintance and friend, in the person of Mr. Patterson, an editor of a newspaper. He exhibited his manuscript to Mr. P. who was very much pleased with it, and borrowed it for perusal... At length the manuscript was returned to its author, and soon after we removed to Amity, Washington county, Pa., where Mr. S. deceased in 1816." Although the widow's 1839 statement does not state the year when they "removed to Amity," it does indicate that a substantial period of time elapsed, after "the year 1812," before the family relocated to Washington County. Again, a late 1814 arrival appears most likely.  A late 1800s view of the Amity "temperance tavern" managed by Spalding and his wife

A late 1800s view of the Amity "temperance tavern" managed by Spalding and his wife

(original photograph computer enhanced to clarify the image) In 1869 Mr. Redick McKee, a former resident of Amity, provided a statement in which he recalled his moving to that village "in the fall of 1814," occupying a local retail store, and boarding nearby at "Spalding's tavern." McKee gives his reader the impression that the Spalding family were settled into their management of that little hotel, well before the end of 1814. McKee's statement also says he then witnessed "Mr. Spalding spending much time in writing... what purported to be a veritable history of the nations or tribes who inhabited Canaan when, or before, that country was invaded by the Israelites, under Joshua." All of which (if true) confirms the fact, that by the fall of 1814, Solomon Spalding was living in Washington County, Pennsylvania, where he was composing pseudo-biblical fiction relating the adventures of ancient Canaanites, their being invaded by attacking Israelites, the military leadership of Joshua, etc. In a subsequent statement Mr. McKee said that he boarded with the Spalding family for "almost two years." In yet another communication, McKee stated that the Spaldings came to Amity in October of 1814 and that he (McKee) began to board with them in November of 1814 -- so his activity in that regard must have continued well into the year 1816. During this period McKee claimed to have "met daily" with the Spaldings' daughter -- but he gave no indication that Mr. Spalding had left his residence at the Amity tavern for an extended period of time, or that the would-be author temporarily moved in with the Hugh Wilson family in neighboring Strabane township. McKee recalled his having left Amity a month or two before Spalding's death. Three distinct possibilities remain open, in the presumed connection of Solomon Spalding with the Hugh Wilson family: 1. Rachel Leet Wilson may have indeed been born in August of 1808, but was prone to understate her true age by a year or two. In that case, she would have been barely old enough to have accurately witnessed Solomon Spalding's lodging with her parents during the winter of 1813-14, before Spalding moved his family to Amity. Perhaps then, her own parents later informed the child of details she had not perceived. Other Considerations Several of the allegations embodied in Rachel Leet Wilson's account are verifiable. Hugh Wilson (1765-1832) was indeed a close associate of Elder Campbell. Both were active in local religious affairs during the period when the Campbells were still in communion with the Baptists. Wilson ran a business in downtown Washington village that was located within easy walking distance of Alexander Campbell's house. Wilson assisted in the construction of the first Baptist chapel in Washington village. He accompanied the Campbells to Pittsburgh in Sept., 1823 to attend the meeting of the Redstone Baptist Association at which Elder Sidney Rigdon was effectively deposed from his Pittsburgh pastorate. Thomas Campbell was the ministerial "messenger" from the Brush Run congregation -- Hugh Wilson was a lay representative from the adjacent Washington congregation -- and Alexander Campbell attended as a mere visitor, having escaped the legal jurisdiction of the Association, before its unhappy leaders could excommunicate him. Hugh Wilson's reputation for public charity was well deserved. The local newspapers of his day document his good efforts in charitable causes. He owned multiple real estate properties in and around Washington village, where he could house and feed down-and-out Baptists, (or reformers, dissidents, former clergymen, etc.). Solomon Spalding need not have been an active, pious Baptist, in order to have received an invitation to lodge with the Wilsons at Locust Hill. Finally, the curious reader might well wonder just what sort of fiction Solomon Spalding could have been composing during his reported stay in the Wilson household. The description offered by Redick McKee (of Canaanites, Israelites under Joshua, etc.) does not match either of the pseudo-histories generally credited to Spalding's imagination -- it does not describe wandering Roman sailors cast up on America's preColumbian shores; nor does it describe Jaredites and Nephites sailing across uncharted seas to occupy a New World's "land of promise." What McKee's summary does resemble is a scenario once presented to his students by Solomon Spalding's old professor at Dartmouth, Dr. John Smith: It appears very probable that this new world was peopled both from Africa and Asia (the northern part). It is almost certain the aboriginal inhabitants of America are not the descendants of Jews, Christians, or Mohametans... |

Return to Top of Page

Old Spalding Library | New Spalding Library | e-mail Site Host

Mormon Classics | Bookshelf | Newspapers | History Vault

Last Revised: Mar. 22, 2012